(This article complements the one on this website about Roy Howard’s False Armistice findings.)

The message in the telegram, purportedly sent on Captain R. H. Jackson’s order to Admiral H. B. Wilson in Brest on 7 November 1918, was an ‘afternoon false armistice report’, wired a few hours after false armistice reports had been circulating in Paris during the morning. It stated that the [French] Foreign Office had announced an Armistice had been signed at 11 o’clock that morning, a cessation of hostilities would occur at 2 o’clock that afternoon, and the US Army had taken the city of Sedan during the morning. It showed “15207” – 3:20 pm on 7 November – as the time the message was issued, and “Jackson” as having authorized its transmission.

As the US Army Intelligence Officer in Brest, Arthur Hornblow spent several hours with Roy Howard on 7 November 1918, and after the war wrote a magazine feature about the False Armistice based partly on his firsthand knowledge of what happened in Brest that day. It was published in November 1921. Many years later, he received a letter from a serving chief petty officer who said that he had been present in the US Navy Paris Headquarters when the false armistice message, carrying Captain Jackson’s name, was sent from there to Admiral Wilson in Brest.

The main part of this article begins with information Hornblow acquired about Jackson in 1921 from Admiral H. B. Wilson; then relates what the chief petty officer told him in their correspondence during 1941 and 1944. It is followed by some clarifying and related details.

Hornblow’s information about the armistice message and its naval telegram sheet

a) From Admiral Wilson, 1921

During June or early July 1921, Hornblow sent Admiral Wilson a copy of ‘Fake Armistice’ – the original version of his account of the False Armistice – and asked him to comment on it. He also sent a copy and similar request to Roy Howard. He was hoping to obtain their approval for what he had written about them and what they did in Brest on 7 November 1918 prior to having it published.1a

Wilson obliged and, replying that he disagreed with “some of [Hornblow’s] facts”, almost immediately referred to his naming of Captain Jackson as the sender of the false armistice message.

Hornblow related in ‘Fake Armistice’ how Roy Howard had told him in Brest that, around 4:00 pm, he and Admiral Wilson “had not been chatting more than a few minutes when an orderly entered with a telegram”. Having read it, Wilson “handed the message to Howard [who] beheld an official communication signed by Commander Jackson, the naval attache at our Paris embassy”, which said “ARMISTICE SIGNED THIS MORNING AT 11 ALL HOSTILITIES CEASED AT 2 P.M. TODAY”.1b

Admiral Wilson made the following significant points:

“[The] message [was] a routine one from my representative in Paris who kept me informed of all reports and rumors. I have never told anyone from whom the message came, other than saying it was from our office there. It is true that one of his functions was Naval Attaché, but those duties were small in comparison with others, and to have the article read that the message was from the Naval Attaché is off, though perhaps technically correct. I feel you do the office of the Naval Attaché an injustice in so expressing yourself. It was from my office in Paris. I hope you see this. I gave it the same credence as the one hundred and one other messages I had received from time to time, some proving correct and some incorrect.”2 (My italics)

In response, Hornblow changed the passage to read that the false armistice message was in an “official telegram, signed by Commander Jackson of Admiral Wilson’s office in Paris and naval attache at our Paris embassy.” And in a later passage discussing Wilson’s acceptance of responsibility for announcing the message, observed that the Admiral “did not even make mention of the official who had sent, or, at least, whose signature was affixed to the erroneous communication from Paris”. (My italics)

When Century Magazine published Hornblow’s article in November 1921, he had amended it in several places to accommodate the comments Admiral Wilson and also Roy Howard had made about it. He had also changed its title to ‘Amazing Armistice’ after Roy Howard advised him not to use fake to describe the 7 November 1918 armistice news.3

b) From Moses Cook, 1941 and 1944

During 1941, by which time Hornblow was an established Hollywood film producer working at Paramount Pictures, he received information about how the Jackson false armistice message reached US Navy Headquarters in Paris and was transmitted to Brest. The information came, unsolicited initially, in letters from Moses Cook, “a press telegrapher in civil life” but then serving as a radio operator with the rank of Chief Petty Officer on the USS Wyoming.

“I . . . sent it originally from Naval Headquarters in Paris”

In April 1941, in his first of four letters to Hornblow, Cook claimed that he was “chief radioman” on duty at US Navy Headquarters in Paris when the false armistice message arrived there on 7 November 1918. Without elaborating, he stated (ambiguously) that he happened to be “the one who sent it originally from Naval Headquarters in Paris”. As verification, he included details about a CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) twentieth-anniversary Armistice programme from New York City in November 1938, in which he “told his unique story” (to radio journalist Gabriel Heatter) “of the tense moments when the [false armistice] news was received and how it was cancelled later”. But he did not mention Captain Jackson or the American Embassy in this first letter.4

He had written, he explained, to request a copy of Hornblow’s November 1921 ‘Amazing Armistice’ article to replace the one in his collection of “stories relative to this Armistice” which a friend of his (Col. W.H. Rankin) had borrowed while writing a book about Roy Howard but subsequently mislaid.

In his replies to this and Cook’s subsequent letters, Hornblow promised to try to find a copy of the 1921 article, and pressed him for details about the false armistice message he said he had handled. He asked him for a “recital of . . . facts” about how the “telegram was filed with [him] and by whom”; “most particularly”, whether Captain Jackson “had anything to do with [it]”; whether the Embassy made any effort “to account for the filing of the wire” after the news was shown to be false; who the officer was who ordered the message to be sent out and why he believed it was authentic; whether “he was an officer of the regular navy or the Reserve; and whether Cook saw him again. Fundamental questions which, if their answers had provided the details hoped for, would have helped resolve some of the mystery surrounding the False Armistice then and now.

The following recounts what Cook wrote in his subsequent letters, and contains extracts from a later newspaper item he also sent to Hornblow.

“Very glad to . . . pass along the story of the ‘False Armistice’ to you as it really happened.”

Cook remarked that, apart from himself, only two other people “knew this story”: “a successful attorney in New York City”, whom he did not name; and “Lieutenant Junior Grade Barler”, Navy Reserve, from Michigan, whose initials he did not recall, and who had died in 1934.

On 7 November 1918, Cook was the “chief radioman in charge of the wire room” [Naval Communication area] at US Navy Headquarters in Paris; Lieutenant Barler was the duty “communication officer”. During the afternoon [no time specified], Barler suddenly rushed into the wire room, handed Cook a message and ordered himto “Get this off right away”.

The message, carrying Captain Jackson’s name, read “Armistice signed eleven am, cease firing two pm, Sedan capitulated“.

Cook asked the Lieutenant where the message had come from; Barler replied that a commander at the American Embassy had just telephoned it to him and mentioned his name to Cook, who told Hornblow he knew the commander but no longer remembered his name. Cook then passed the message to the “operator who was sitting on the Brest Wire” (unnamed), told him to stop what he was doing (“sending the American casualty list of the killed and wounded as we did every afternoon”) and transmit the armistice bulletin, which the operator did straight away.

Some twenty minutes later, Barler rushed back into the wire room and shouted to Cook not to send the message: “For Gods sake stop that message . . . . Its a fake”. Cook pushed the operator’s hand away from the transmitter, “grabbed the key and asked Brest if they could stop the message”. But it was too late – the message had already been forwarded from Brest to Washington, DC.

As well as being American Naval Attaché in Paris, Captain Jackson was commanding officer at Navy Headquarters. Cook was “very certain that he knew nothing about this message” and did not authorize it even though his name was attached to it: “all messages leaving our headquarters had to be signed ‘Jackson’ as a matter of routine, but he did not see every dispatch that was sent”. Indeed, “he was very much upset about it”, demanded to know what had happened and who had released it, and had Lieutenant Barler “on the carpet about it”.

Years later, just prior to Cook’s participation in the November 1938 CBS Armistice anniversary programme, CBS contacted Jackson, by now an admiral, to ask permission to use his name in connection with the false armistice message. He emphatically refused, threatening to “bring suit” against CBS if they did. Consequently, during the programme he was referred to only by his title of naval attaché. “I am very certain”, Cook maintained, “that he knew nothing about this message”.

Cook believed that Lieutenant Barler was duped into thinking the telephone call was from the Embassy when it was “probably the work of an enemy agent” aiming “to give the world a taste of what an Armistice was like” – and making “a good job of it”: “the fault was with the Lieut. How in the world did he fall for a thing like that over the fone?”

Cook’s suspicions were aroused as soon as Barler told him how the message had arrived from the Embassy. He wanted “to bring out” that the Embassy “never foned that message”, “knew nothing of it, and were never able to locate the party that did . . . . I have never heard of anyone coming forward and saying that they were the one who foned that message to Naval Headquarters”. And why, he wondered, would they “fone such an important message? Why did’nt they put it in code? They coded other messages of less importance, and why was’nt it delivered by a marine courier as were all messages of any urgency? The American Embassy was right behind the Navy Headquarters building. Also I did’nt believe that the Germans had met Foch so soon and to have talked things over so quickly”.

Cook did not see Lieutenant Barler again. Not long after these events, Barler was sent home, seemingly because of his part in them: “he simply believed that the telephone call was genuine”. Shortly after the Real Armistice Cook was sent to Italy for a month, then to Brest for about seven weeks; here he was “put in charge of the brig” before returning to the United States.

Contacting Hornblow again in 1944, by which time he was a warrant officer and “chief radio electrician at the Miami Naval Air station, Opa Locka”, Cook sent a cutting of an item about himself from the Miami Daily News with the title ‘Inside Story of False Armistice Flash In 1918 Told By Navy Man Here’. In his interview for the item, Cook repeated the account of 7 November events at Paris Navy Headquarters he had related to Hornblow, but with an additional conjecture about the origin of the armistice message:

“That will probably always remain a mystery, Cook says. It has been well established that it did not originate in the American embassy. Cook’s own theory is that a clever German agent ‘phoned in the message to the communications system, imitating the voice of the commander, who, the lieutenant [Barler] said, dictated [it] to him [from the embassy].”

Cook’s “own theory” – that the armistice message was German disinformation – echoed what Hornblow had surmised in his ‘Amazing Armistice’ article and may well have been indebted to it. On the other hand, Cook’s proposition – that a clever German agent imitated the voice of a commander at the American Embassy in Paris and thereby fooled Lieutenant Barler at Navy Headquarters into believing the false peace news – quite possibly struck Hornblow as being obviously contrived and comically implausible.

In a brief acknowledgment – the last of their letters in the archive – Hornblow thanked Cook for the “interesting clippings on [the] Armistice dispatch”. He was “glad to have them” for his files, he said, and to learn that Cook was “still well and active in the service”. (Whether he ever sent Cook a copy of his November 1921 article is not indicated in their correspondence.)5

Clarifications and related details

Captain R.H. Jackson

Captain Jackson had arrived in Paris in June 1917 as the “Representative of the United States Navy Department”, “senior United States Naval Officer on shore in France”, commander of US “naval and aviation bases” in France, and commanding officer at the US Navy Headquarters in Paris. In these capacities, he acted under the orders of Vice-Admiral William S. Sims, the Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters whose headquarters were in London. He was also Sims’ liaison officer at the French Ministry of Marine in Paris, and was instructed to “confer” with Admiral H. B. Wilson at US Navy Headquarters in Brest when the latter became “Senior Naval Officer afloat in French Waters” during late October 1917.

When Jackson arrived in Paris, the Naval Attaché at the American Embassy (since 1915) was Lieutenant Commander (later Captain) W. R. Sayles who was promoted in January 1918 to the new post of “Intelligence Officer of the United States Naval Forces in France”. Jackson, retaining his other responsibilities, became Naval Attaché in June 1918 and “Liaison Officer between [Admiral Wilson in Brest] and the French Authorities in Paris”. As Wilson’s Liaison Officer, he was considered to be a member of Wilson’s own staff – there was “considerable official and semi-official” daily communication between Brest Navy Headquarters and what Admiral Wilson described to Hornblow as his “office in Paris”.6a

Moses Cook told Hornblow that Jackson was “in command of the US Naval Headquarters in Paris and as such was the American Naval Attache there . . . . He was referred to as Commander at times because he was Commanding Officer, but he was above a Commander”.

Throughout his time in Paris, Jackson’s office and base was in the US Navy Headquarters building not far from the American Embassy. As the new Naval Attaché, his official base and offices were in the Embassy; but he delegated Assistant Naval Attaché (since October 1917), Lieutenant Commander Charles O. Mass, to carry out his duties there.6b

Cook’s opinion (above) that Captain Jackson did not authorize the armistice message before it went out appears to substantiate Admiral Wilson’s remark to Hornblow that the statement in Fake Armistice about the Naval Attaché sending the telegram was “off, though perhaps technically correct . . . . It was from my office in Paris. I hope you see this”. Because the remark becomes clearer if someone in the Naval Attaché’s Embassy office sent the false armistice message to Jackson’s Navy Headquarters office, and, in Jackson’s absence, decided to transmit the message to Brest with his name as authorization.6c

Moses Cook

No information about Moses Cook’s service in the US Navy during the first and second world wars has so far been located from official military publications. As he was not a commissioned or warrant officer, no ‘Moses Cook, chief radioman’ is shown, for instance, in the 1918, 1919, or 1941 US Navy Lists. The information about him here is solely from the letters and news clippings he sent to Arthur Hornblow.

Lieutenant Barler

According to Cook, Lieutenant Barler wrote down the 7 November armistice message, as telephoned from the American Embassy, ordered its transmission to Brest, and about twenty minutes after it had left Paris tried to cancel it; but that by then the message had already been forwarded from Brest to Washington, DC.

The only Lieutenant Barler listed in the US Navy Register for that time is: “Barler, Harold A.C., Lieutenant (j. g.) [junior grade] U.S.N.R.F., born 18 May 1886, enrolled 23 September 1917”.7

The unnamed operator of the Brest Wire

Cook told Hornblow that Barler died in 1934, leaving just himself and the operator of the Brest Wire as “the only ones that were present” when the armistice message was transmitted. He noted that he regularly kept in touch with this operator, but did not name him, referring to him variously as “my friend”, “a successful attorney in New York City”, and “a young sailor, now a prominent New York attorney”.

This unnamed operator of the Brest Wire was Lieutenant Emmett King, who described himself as “Chief Electrician (Radio)” at Navy Headquarters in Paris in a letter from December 1918 among Roy Howard’s papers.8 After a number of Internet searches, references to “Emmett King . . . an attorney living in New York” have been located in the transcripts of investigations carried out by the US Senate, shortly after the end of the Second World War, into “Expenditures in the Executive Departments”. Apparently, King took part in a business trip to Paris in July 1945 with two other men, spoke French, “represented the Albert Verley Co. in New York”, and was advising on the negotiation of contracts with “manufacturers of finished perfumes”. His full name is indexed as “Emmett Miles King”; he was 52 in 1945, and therefore 25 in 1918.9

In his December 1918 letter which was forwarded to Roy Howard, King did not specify that he was operating the Brest Wire on 7 November 1918, but he affirmed that he “flashed the [false armistice] message”, knew “what caused the whole affair”, and “handled the whole case”. He explained that the message read “identically the same as the message that was afterwards published in America to the effect that hostilities had ceased”, and that it was handed to him “in plain English” at about 3:50 pm (French time). But he did not say where it came from (the American Embassy, French Foreign Ministry, French Ministry of War, for instance) only that it was “absolutely from official channels; did not reveal whose name it carried as authorization; or specify to whom and where he “flashed” it. But he did disclose that almost immediately after sending it, the message was taken from him and was “never returned to the files”; that “the whole affair” had been caused by a “government official” – not an American, he pointed out – who had made some foolish mistake which could not be made public.8

US Navy Headquarters in Brest

Moses Cook told Hornblow that he spent seven weeks in Brest before finally leaving France early in 1919. It is reasonable to assume that he became acquainted there with an unnamed wireless operator at Admiral Wilson’s Headquarters who, L. B. Mickel told Roy Howard, had made a copy of the Jackson False Armistice Telegram. And it is possible that Cook also met Lieutenant J. A. Carey, Admiral Wilson’s secretary, who, Hugh Baillie (a United Press President later on) had told Howard, was offering to sell “the original” telegram.8

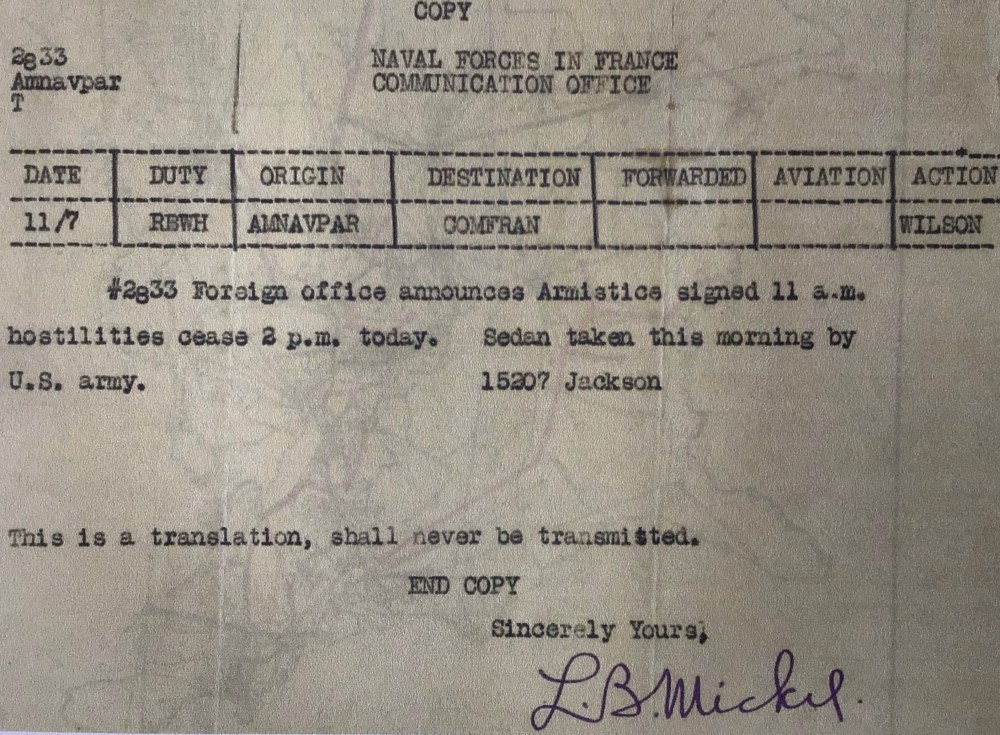

The following is an image of a typed-out copy of the Jackson False Armistice Message on a Brest naval telegram sheet that L. B. Mickel sent to Roy Howard in August 1919. (Mickel worked for United Press for many years, becoming its “Superintendent of U.S. Bureaus”.)8 It is not known whether Hornblow ever saw Jackson’s message in its telegram version.

© James Smith. (Reviewed and with additional information, July 2024. Uploaded, reorganized, reviewed, February 2019-December 2021.)

REFERENCES

ARCHIVE SOURCES

I. ‘Arthur and Leonora Hornblow Papers’. Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Beverly Hills, California.

II. ‘Admiral Henry B. Wilson Papers’, Box 1. Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

ENDNOTES

1a. ‘Fake Armistice’ is not available in Hornblow’s or Howard’s archives, but the copy he sent to Admiral Wilson is preserved in the latter’s papers.

1b. ‘Fake Armistice’, p8. (Admiral Wilson Papers)

2. Letter: Admiral Henry B. Wilson to Arthur Hornblow. 13 July 1921 (Sheet 1). (Hornblow Papers; and p2 of Admiral Wilson Papers) Hornblow was the first to state publicly that Captain Jackson sent the armistice message to Brest.

3. ‘The Amazing Armistice: Inside Story of the Premature Peace Report’, in The Century Magazine, November 1921, pp94 and 97.

With clear reasoning Howard pointed out that “Inasmuch as the idea of a fake story involves palpable and deliberate intention to deceive, and inasmuch as your article makes clear that there was no such intention on the part of the newspapers or the newspapermen, I feel that your purpose would be better served and an unintentional injustice avoided by the substitution of another term for the word ‘fake’”. (Letter: Roy W. Howard to Arthur Hornblow. San Diego. June nineteenth 1921, p2. Hornblow Papers)

4. First letter: Moses Cook to Arthur Hornblow, 20 April 1941; with a piece about him from The Norfolk Seabag, 2-8-41, under the heading ‘Reserve C.P.O. Had Unique Experience’. (Hornblow Papers)

5. Subsequent correspondence: Arthur Hornblow to Moses Cook, April 28, 1941; Moses Cook to Arthur Hornblow, 7th May, 1941; Arthur Hornblow to Moses Cook, May 14th, 1941; Moses Cook to Arthur Hornblow, May 23, 1941; Moses Cook to Arthur Hornblow (July?) 1944. This letter is not in the collection but is acknowledged in Arthur Hornblow to Moses Cook, 31 July, 1944; its enclosure from The Miami Daily News, 20 June 1944, under the heading ‘Inside Story of False Armistice Flash in 1918 Told by Navy Man Here’ is in the collection. (Hornblow Papers)

6a. See also the ‘Richard H. Jackson. (1866-1971)’ entry in the Biographical Details article on this website.

6b. Lieutenant Commander Charles O. Maas compiled A History of the Office of the United States Naval Attaché, American Embassy, Paris, France, during the period embraced by the participation of the United States in the war of 1914-1918, for the US Navy’s Historical Section. Many of the details here about Captain Jackson are from this history. Its unbound typewritten pages are held by the US National Archives and Records Service, Washington, DC. (File Unit, E-9-a, 12302. NAID, 196039947 and 196039948, Container ID 745, Record Group 38. The separate typewritten pages were put together as a Print Book in 1977. Maas died in France on 21 July 1919, what must have been a short time after he completed the history. (Brief entry about him in the Columbia University Archives, under Law School, Class Year 1892.) In the Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps, January 1, 1919, pp711;1171, he is listed as “Charles Oscar Maas, born 28 Nov. [18]70. Lieut. Commander U.S.N.R.F. Enrolled, 27 Aug. [19]17.

In his History of the Office…,there is nothing about the False Armistice or what happened in the American Embassy and Navy Headquarters on 7 November 1918.

6c. See ‘The Jackson False Armistice Telegram’ in the False Armistice Cablegrams from France article on this website.

7. Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps, January 1, 1919, p650.

8. See Roy Howard’s Search for Information about the False Armistice, on this website.

9. Influence In Government Procurement. Hearings Before The Investigations Subcommittee Of The Committee On Expenditures In The Executive Departments. First Session; pp225, 227, 763. (Washington 1949)