The arrangements the French and Germans made to ensure that the German armistice delegation crossed the Western Front safely on its way to confer with Supreme Allied Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch are an integral part of the historical context of both the False Armistice and Real Armistice of November 1918. This is an account, in two parts, of those arrangements: the first describes 6-7 November events and activities on the French side of where the delegates crossed the lines; the second describes those on the German side.

Orders about their respective arrangements passed from the High Commands on both sides of the front lines to their commanders and forward units in the broad area around where the delegates were to cross the lines. French orders and activities covered arrangements for halting the delegation safely at the crossing-point and taking it on to Marshal Foch in Rethondes. German orders and activities primarily concerned French cease-fire arrangements at the crossing-point, to which they objected.

Inevitably, during 7 November rumours about the delegation leaked out and started spreading among French and German troops around the crossing-point area; and for most of the time before the delegation finally arrived there was uncertainty on both sides about what was actually happening. Consequently, misunderstandings occurred and misleading, erroneous information arose and circulated on both sides – the immediate circumstances of the 7 November false news that the German armistice had been signed and the war had ended that day.

On the French Side of the Crossing-Point

[To try to avoid confusion, the times given in this part of the account are French/Allied times, one hour behind German time in November 1918. Any German times that are included – for instance from the Spa telegrams to Senlis – have been converted to the French equivalent and are shown in italics. For example, ‘3:00 pm and 4:00 pm’ indicate the German times of 4:00 pm and 5:00 pm.]

On Wednesday 6 November, Marshal Foch’s Headquarters in Senlis sent the Allied Commanders – General (soon to be Marshal) Philippe Pétain, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, General John Pershing, and King Albert I of the Belgians – an encrypted telegram about the German armistice delegates. General Edmond Buat, Chief of Staff at Pétain’s Headquarters in Provins, relayed the telegram to the headquarters of the others, recording in his diary: “at 10:30 pm an order from Marshal Foch to forward the following telegram to the armies: If the [German] delegates present themselves at our lines, they are to be stopped [and held] at the forward positions; their status and their purpose are to be reported to the marshal, without any delay [and] by the fastest route. They are to be held there until the marshal’s reply becomes known.” Instructions presumably prompted by the official German press release earlier that day that an armistice delegation had left Berlin for the Western Front. NOTES 1a. 1b

(General Pershing’s Headquarters circulated the order to American front-line forces at 6:00 am on 7 November. The A.E.F. Second Army’s 33rd Division, in the Troyon-sur-Meuse sector (a few miles south of Verdun), received it at 10:40 am.1c. 1d)

The same night, between 11:00 and 11:30 pm, the first Spa telegram arrived at Marshal Foch’s Headquarters in Senlis. In German and plain Morse Code, it informed him that five German delegates, with assistants, would be travelling by motor car to the Western Front to start talks about an armistice, and suggested that, “in the interests of humanity”, hostilities should be suspended when the delegates reached the Allies’ lines. It had been picked up and forwarded to Senlis by duty operators in the Eiffel Tower radio station. General Émile Riedinger, the French Second Bureau (Deuxième Bureau) Intelligence Chief in Senlis took it straight to General Maxime Weygand, Foch’s Chief of Staff. Weygand drafted the French reply, which Foch approved. It was telephoned to Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s Office and to his residence at the Ministry of War (he was also Minister of War), and was eventually released, for the Germans to pick up, at 2:30 am and again at 3:00 am in the early morning of Thursday 7 November.1e

Foch’s reply, in French and plain Morse Code, directed the delegates to arrive at the French forward positions on the road from Chimay (in German-occupied Belgium) to Fourmies, La Capelle and Guise (still in occupied French territory but from which the Germans were now retreating). They would be met there and taken elsewhere to meet him. The request for hostilities to be suspended was ignored.1b

(Radio operators at the American Second Army’s 33rd Division Headquarters received the information at 2:40 am, probably from Pershing’s Headquarters. The Division’s G-2 Office recorded that “the German plenipotentiaries desire to meet Marshal Foch to ask him for an armistice. They will have to present themselves at the French outposts coming by the road Chimay-Formies-La Capelle-Guise. Orders have been given to receive them and to direct them to the point of rendezvous”.1d)

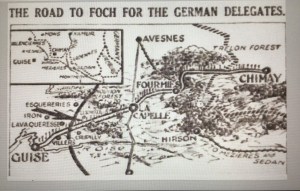

Sketch Map: Marshal Foch’s Designated Road

The road was in north-east France and close to the Belgian border, in the operations area of General Marie-Eugène Debeney’s French First Army and, on the German side, that of General Oskar von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army. (On Debeney’s left was General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s British Fourth Army; on his right was General Georges Louis Humbert’s French Third Army.) The delegation’s crossing-point would be where the French forward positions happened to be when it arrived.

The following map, showing some geographical details of the designated road’s vicinity, was published in the (London) Daily Express newspaper the following day.1f

Another British newspaper explained that “the road indicated by Marshal Foch runs north-east from the junction of Guise, captured this week by the French, to La Capelle, and on to Fourmies, both of which towns are also road and rail centres. Thence the road skirts to Trelon Forest and Chimay Wood to the town of Chimay”.1g

Arrangements for the armistice delegation

As the day began on 7 November, the French front lines were just forward of the village of Buironfosse, a short distance south-west of the town of La Capelle, still held by the Germans but against which the French were due to resume their advance at 6:00 am.

Some four hours earlier, around 2:00 am, General Debeney at French First Army Headquarters, then in Beaulieu-les-Fontaines (south-west of Guise), was told that a German armistice delegation would be heading for his front lines on the Chimay-La Capelle-Guise road, and instructed to send one of his staff officers to his forward positions to arrange to meet it. Commander François de Bourbon-Busset, Debeney’s Headquarters Second Bureau Chief, was given the task and instructed to leave for the front before 8:00 am. As Marshal Foch had ordered the overall offensive against the Germans to continue, Bourbon-Busset was to make sure the German delegates crossed the lines safely and then take them to First Army Headquarters, which were about to move forward to Homblières. He set out for Buironfosse-La Capelle by car not long after 6:30 am, expecting to receive details later about the delegates’ arrival time at the Front.2

General Debeney had the armistice delegation information relayed to General Paul Toulorge, Commander of the First Army’s 31st Corps whose Divisions were leading the French advance in the broad area of the designated road. Toulorge passed the news on to his Corps Divisions’ Headquarters, one of which was that of General Paul Cabaud’s 166th Division at Villers-lès-Guise, not far along the road from Guise to Buironfosse and La Capelle. But as well as sending him the news, Toulorge instructed Cabaud to send an officer from his 166th Division Headquarters to meet the German armistice delegates at his forward positions. The officer – a Captain Le Lay – set out for Buironfosse-La Capelle without delay.

‘Delegates arriving around 8:00 am’ (misinformation)

At 6:30 am, before Commander Bourbon-Busset had left First Army Headquarters for the Front, Captain Le Lay arrived at Buironfosse with ‘top-secret’ information from General Cabaud for Commander Ducornez, whose 171st Infantry Regiment units were leading the advance against the Germans. Cabaud informed Ducornez that he should expect German armistice delegates to arrive along the road between Buironfosse and La Capelle around 8 o’clock that morning, and that he must prepare immediately for them to cross the French lines.3

Cabaud’s information for Ducornez conflicted with General Debeney’s information about the German delegation and his orders to Bourbon-Busset: Debeney had not stated an arrival time for the delegation; Cabaud’s “about 8:00 am” arrival time was erroneous. And Debeney had been told to send an officer from his own First Army Headquarters to meet the delegation, not from a Corps or Division Headquarters. (The errors likey arose from some ambiguity in or confusion over the relayed delegation information from Debeney to General Toulorge.)

Commander Ducornez immediately started preparing for the German delegation to cross his lines unhindered. He sent a messenger with the news to Captain Marius Lhuillier, commanding the 1st Battalion of the 171st Infantry Regiment which was providing the forward units towards La Capelle. Very soon, and “with lightning speed” (“avec la rapidité de l’éclair”), rumours about an armistice were spreading among Ducornez’s men.4

Around 7:30 am, Captain Lhuillier dispatched the delegation information to Lieutenant Édouard Hengy, acting commander of forward units from the 1st Battalion’s 3rd Company. A German motor car, he told Hengy, would be arriving near La Capelle at about 8:00 am; he ordered him not to fire on the car but to stop it when he saw a white flag, and not to tell his men what was going to happen until the last moment.5 When the armistice delegates failed to arrive, Captain Lhuillier ordered Hengy at 8:30 am to hold his positions, not to advance further for the time being, but to send out reconnaissance patrols and report back.6

So, well before 8:30 am on 7 November, French forward units around the road to La Capelle had already been placed on alert; and misinformation about the arrival of the German delegation was spreading rapidly among those units. Meanwhile, on the other side of the front lines the German delegates were about 124 miles away in Spa, at Army Supreme Command Headquarters in the Hotel Britannique. And it would be a few more hours before they left from there for the designated road and a crossing-point.

‘Delegates arriving at midday’ (more misinformation)

Nearly two and a half hours after leaving First Army Headquarters, Bourbon-Busset finally located Commander Ducornez in La Capelle, which had only just been cleared of the enemy. He caught up with Ducornez in the town’s main street sometime before 9:00 am, explained why General Debeney had sent him, and must have discussed General Cabaud’s erroneous information about the delegation’s 8:00 am arrival and the arrangements Ducornez had already made for his forward units to meet it.7

At some point before midday, General Debeney sent four staff officers from First Army Headquarters (now moved forward to Homblières) to join Bourbon-Busset in La Capelle. The officers carried the misinformation that the armistice delegates would arrive around midday.8 The British (and presumably the Americans) also had this news: at Field Marshal Haig’s Headquarters in Montreuil, a staff officer noted in his diary: “The German [delegation] is expected to cross the line at 12 noon and to be at Foch’s Headquarters at Senlis at 4pm to receive the terms of the Armistice. All firing ceased on the road to Guise by which [the delegation] is expected from about 10 am. The air was thick with rumours.”9

The source of this midday-arrival detail seems to be a telegram from Spa Supreme Headquarters to General Max von Gallwitz, which the Allies apparently intercepted. But as ‘midday’ was the time specified in the telegram, the Allies appear to have circulated the detail without taking into account that German midday was 11:00 am for them. (See below, ‘It will reach the Front at Midday’ under “On the German Side of the Crossing-Point”.)

Midday cease-fire in La Capelle

The four staff officers General Debeney sent to La Capelle from First Army Headquarters travelled in four French motor cars that were to be used later to take the German delegates to General Debeney at Homblières. At what time they arrived is not certain (the journey should have taken no more than two hours) but the midday-arrival news apparently reached La Capelle before they did. In any case, as midday approached, Bourbon-Busset and Ducornez agreed that the forward units around La Capelle should now halt their advance and stop firing. They issued instructions to that effect without informing the Germans of their cease-fire.10

‘Delegates arriving between 4:00 pm and 5:00 pm’

Also at midday, General Debeney’s First Army Headquarters telephoned new information and new instructions to La Capelle, which were probably relayed via the headquarters of other units in the vicinity.11

The new information was that the German delegation was headed by Secretary of State Erzberger, that ten people, plus drivers, were in the group, and that it would reach the French lines between 4:00 and 5:00 pm. Debeney’s new instructions were that the delegates should not be blindfolded, their German motor cars and drivers were to remain at La Capelle, and Commander Bourbon-Busset was to accompany the delegates to First Army Headquarters in the four French vehicles sent for the purpose.12

(The details about the delegation’s composition are from the second Spa-Senlis telegram sent from Berlin at 11:00 am. This, however, gives the precise arrival time at the Front of 5:00 pm German time/4:00 pm French time. Interestingly, General Edmond Buat, Chief of Staff at General Philippe Pétain’s French Armies Headquarters in Provins, noted in his diary for 7 November 1918 that the Germans announced that the delegation would cross the lines between “2 et 4 heures” – French time.13)

At 11:30 am, the Germans transmitted their third Spa-Senlis telegram announcing that an order had been given to cease firing on the Front from 2:00 pm, until further orders, to enable the delegation to cross the lines; and that road menders would be accompanying the delegation to repair the damaged La Capelle road.14 Surprisingly, none of the French sources cited here indicates that this particular Spa message was relayed to La Capelle, that it was received there or, therefore, that Bourbon-Busset and Ducornez became aware that the German High Command had ordered a cease-fire from 2:00 pm in the area where they were now expecting the delegation to arrive between 4:00 pm and 5:00 pm.15

German 12:30 pm cessation of hostilities

Starting shortly after midday, at various points manned by French forward units, groups of Germans approached wanting to fraternize, while others, holding back, waved their arms and shouted that an armistice had been signed and a cease-fire was starting at 12:30 pm. Where Lieutenant Hengy happened to be, a French civilian (an old man) approached saying that a German officer had sent him to tell French troops he wanted to talk to them.16 As the afternoon progressed, several other reports arrived from the forward units about German troops trying to fraternize. Captain Lhuillier reported the incidents; Commander Ducornez ordered him to halt his units, take prisoner any Germans who approached their positions and avoid fraternizing with them. By three o’clock, more than 400 had been taken prisoner.17

(General Weygand, who was with Foch on 7 November, recalled the incidents several years later and commented that the German troops had tried to fraternize with French forces because they were desperate for the war to end, and either believed or just pretended that hostilities had ceased.18)

French 1:00 pm cessation of hostilities

Commander Ducornez later wrote that he reported the Germans’ behaviour to General Cabaud at 166th Division Headquarters and asked for instructions. And recalled that he received a message around 1:00 pm (“13 heures”) that Division had ordered a cessation of hostilities with effect from 1:00 pm until midnight – that is, about an hour after he and Bourbon-Busset had ordered their midday cease-fire.19

Whether Ducornez was given any other details about the order is not known, but on the same matter, though with different time details, General Buat’s 7 November entry in his diary notes that, in reply to German requests for French troops to cease firing towards a zone from Étroeungt to Ohis (on their side of the lines), they were told that there would be a French cease-fire from midday to 6 o’clock covering only the road where the delegation was due to cross the front lines. When the delegation’s arrival was delayed, the time-limit was extended to midnight (on the 7th), and then to 6:00 am on 8 November.20

Whether the French communicated this cessation of hostilities order to German Supreme Command Headquarters in Spa is not certain; if they did, it was not among the 7 November Spa-Senlis telegrams released to and published in Allied newspapers. It would have been relayed to French First Army Divisions and their units by (non-public) telegraph-line and telephone systems.

The French 3:00 pm order delineating their cease-fire zone

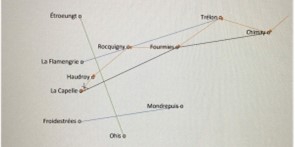

At 3:00 pm, “to facilitate the arrival of the German armistice delegates”, Marshal Foch’s Headquarters ordered that, until midnight, no firing was to be directed from the La Capelle sector into the German-controlled area between a line from La Flamengrie to Trélon in the north and one from Froidestrées to Mondrepuis in the south. The order was relayed to the crossing-point area by the French weather station “MAX”, situated in the Noyon Region north-east of Paris. At 6:30 pm, and sent by “MYZ”, it was renewed until 6:30 the following morning, Friday 8 November.21

Sketch Map: Cease-Fire Zones.

(German cease-fire line (green): Étroeungt to Ohis. French cease-fire zone: between blue lines La Flamengrie to Trélon, and Froidestrées to Mondrepuis.)

This French 3:00 pm cease-fire zone extended over a larger area than that Ducornez and Bourbon-Busset had set around the La Capelle forward positions at midday; but covered a smaller area than the German Étroeungt to Ohis line encompassed. It left ample space, however, for the German delegation to make its way safely towards the front lines from a number of directions.

Why Foch did not order it at 2:00 pm to coincide with the Germans’ 3:00 pm cease-fire announced in their third Spa telegram to Senlis is not known here. But the French profited from their later start and the larger area covered by the German cease-fire zone extending from Étroeungt to Ohis towards and across the front lines. How far across it extended is not certain (or especially pertinent), but after 2:00 pm French time/3:00 pm German time, German forces and occupied territory inside their cease-fire zone but outside the areas around French forward positions at La Capelle, were still vulnerable to French advancing forces. Even after the 3:00 pm French cease-fire zone came into effect, German forces north of La Flamengrie and south of Froidestrées were still exposed.

German protests

“They [the Germans] . . . are demanding a cease-fire . . . along lines chosen by them. Reply: all arrangements have been made for the safety of the plenipotentiaries.” 22

Around 3:30 pm, a German officer and two soldiers, on horseback and showing a white flag, approached the outskirts of La Capelle and were stopped at the French forward positions. Lieutenant Hengy was in charge there, and the German officer, a Lieutenant von Jacobi, first informed him that the armistice delegates were being delayed by the damaged condition of the roads and would not now arrive by 4:00 pm (the arrival time mentioned in the second Spa-Senlis telegram); and then protested that although German troops had ceased hostilities from their positions since the early afternoon, the French troops facing them had not.23

Replying, Lieutenant Hengy showed von Jacobi his written orders to take prisoner any Germans who approached his positions, and not enter into discussions with them. Von Jacobi agreed to accompany Hengy to the rear; on the way, Captain Lhuillier unexpectedly turned up and von Jacobi repeated his message and protest to him. The Captain took note and eventually allowed the Germans to return to their lines.24

(When the armistice delegates arrived later that evening, Lhuillier, Hengy, and von Jacobi met again: having been detailed to accompany the delegates to the French positions, von Jacobi presented Lhuillier and Hengy to General von Winterfeldt, the superior German military delegate.)

Bourbon-Busset and Ducornez moved from Ducornez’s Headquarters in La Capelle to Lhuillier’s forward command post, believing the delegates would now be arriving after 4:00 pm; they returned to La Capelle around 6:00 pm when it became clear there would be further delays. Soon after returning, a German motor car, carrying a white flag, stopped outside the Headquarters building. A Major von Behr, one of three officers in the car, had been sent from Rocquigny with a letter from his commanding officer, General von Anwarter, for the French commander in the town. Bourbon-Busset took it and read it. Complaining that French troops had continued firing and taking prisoners even though his own forces had halted hostilities at 12:30 pm, von Anwarter wanted assurances that the French would safeguard the armistice delegation when it reached the front lines.

Bourbon-Busset replied that his orders were to implement a cease-fire specifically for the safety of the delegates, in the La Capelle sector only – what a disappointed von Behr considered to be merely a ‘partial’ cease-fire. Perhaps to reassure him, Bourbon-Busset invited von Behr to remain with him until the delegates arrived. The Major accepted.25 (It is not clear whether Bourbon-Busset’s reply implied that he had not received the 3:00 pm order from Senlis defining the French cease-fire zone, or that he regarded the defined zone as being within the La Capelle sector, but the latter is more likely.)

The Germans also complained to General Debeney himself that his front-line troops were disregarding the German cease-fire. A wireless message to him at First Army Headquarters, noting that a German cease-fire had been in place since 2:00 pm from Étroeungt to Ohis, requested him to pull back those troops who had continued advancing after the German cease-fire and apply the same German coordinates to a French cease-fire zone. The message was from General von Hutier, the commander of the German forces facing Debeney’s French First Army, and was received at 6:50 pm. Replying at 9:15 pm, Debeney insisted that in accordance with orders given to him, he had already made his arrangements for the safe arrival of the German delegates and would not be making any additional ones.26

By the time Debeney’s reply was transmitted and would have been received by von Hutier, the delegates had already arrived and were safely behind the French lines.

The delegates’ arrival

Sometime before 7:00 pm, information from the fourth Spa telegram to Senlis (transmitted at 4:30 pm) was sent to La Capelle. It advised that, because of delays, the delegates would not be able to cross the front lines at Haudroy until between 7:00 and 9:00 o’clock that evening.27

The hamlet of Haudroy was a short distance from La Capelle on the road leading to the small town of Rocquigny where General Anwarter had his headquarters. In November darkness and a dense mist, the delegates had arrived at Rocquigny not long before 8:00 pm, and reached Haudroy, still occupied, not long before 8:20 pm. From here, their five cars moved slowly towards La Capelle, headlights blazing, flying three white flags, and with a bugler on the running-board of the leading vehicle sounding their cease-fire.

Captain Lhuillier stopped the leading car at his forward positions, noting that the time was exactly 8:20 pm. After a brief exchange between him and General von Winterfeldt, the delegates were taken first to La Capelle – with a French bugler now sounding a French cease-fire – where they met Bourbon-Busset, Commander Ducornez and other staff officers.

Speaking to General von Winterfeldt, in an allusion to Major von Behr’s complaints, Bourbon-Busset told him that, earlier in the day, three German staff officers had arrived at his forward positions convinced that the armistice had already been signed; the officers, he added, were still with him. “Hostilities have been temporarily halted in this sector”, he continued, “but we understand that they will resume two hours after your delegates leave here”. The General replied that it was undoubtedly a “misinterpretation” (on the part of the German officers) and Commander Ducornez remarked that the cease-fire was “only in this sector, and only until midnight”. Major von Behr and his accompanying officers were then brought to meet von Winterfeld.

The delegates left around 10:00 pm, in the French cars sent earlier, for General Debeney’s Headquarters some distance away in Homblières. From here they were driven to Tergnier for the train journey to Rethondes. They finally met Marshal Foch during the morning of Friday 8 November. In the meantime, at 11:00 pm, Captain Lhuillier finally received the (6:30 pm order) to extend the cease-fire in his sector from midnight until 6:00 am the following day.28

(Marshal Foch and his Senlis Headquarters staff waited twenty hours for the delegates’ to cross the front lines, from the time they received the first Spa wireless telegram requesting a meeting with the Marshal; and a further nine hours or so before the initial meeting took place at Rethondes. For the French First Army units along the designated road, the waiting for the delegates’ cars to appear at their forward positions was almost as long. The French public, as a whole, were oblivious to all this; for them the day meant that their long wait for the Germans to make peace had finally arrived.)

Sketch Map: Onward Route

On the German Side of the Crossing-Point

[The times in this part of the account are German times – one hour ahead of French/Allied time in November 1918. Some have been converted from French times and as such are indicated in italics. For example, ‘after 3:30 am and again after 4:00 am’ are the German times for ‘after 2:30 am and again after 3:00 am’ French times.]

Marshal Foch’s reply to the first Spa-Senlis telegram, specifying where the armistice delegates should cross the front lines would have been picked up by the Nauen radio station near Berlin after 3:30 am and again after 4:00 am on 7 November and relayed to German Army Supreme Command Headquarters in Spa (in occupied Belgium). Information and orders concerning the delegation were then sent to military units in the crossing-point area which were part of General Oskar von Hutier’s German Eighteenth Army.

The delegates to assemble in Spa

The first Spa telegram named five armistice delegates: Secretary of State Matthias Erzberger, Count Alfred von Oberndorf (former minister plenipotentiary in Bulgaria), General Detlev von Winterfeldt (former military attaché in Paris), General Erich von Gündell, and Navy Captain Vanselow.14 The first three left Berlin by train at 5:00 pm on Wednesday 6 November to join the other two at Supreme Command Headquarters in Spa. They arrived in the town, to the south-east of Liège, at 8:00 am the following day, fifteen hours later.

‘[They] will reach the Front at midday’ (misinformation)

Just over an hour and a half after the three delegates arrived in Spa, General Max von Gallwitz was notified that an armistice delegation was on its way to meet the Allies and would cross the front lines in the vicinity of Guise at around midday. Von Gallwitz’s Army Group, facing the Americans in the Meuse-Argonne region of the Front and some distance south-east of the La Capelle sector, was not directly involved in preparations for the delegation. But he received the following telegram about it from Spa:

“GROUP OF ARMIES GALLWITZ, November 7, 1918.

9:35 a.m.: Supreme Headquarters (Major von Stuelpnagel) . . . Major Bramsch. Supreme Headquarters is oriented on situation. The Group of Armies is informed that toward noon the Armistice Commission will cross the lines in the vicinity of Guise. The situation requires holding the position at all costs, as otherwise the armistice negotiations might be made very difficult. It is necessary for the Group of Armies to concentrate all reserves at its disposal, in order to contest every enemy success.”

Other German Army Groups must have received similar telegrams at the same time. Indeed, the basic message – “that the front must be held at all costs [during the armistice talks], and that the occupied ground must be defended under all circumstances” – had gone out periodically from Field Marshal Hindenburg at Spa Headquarters since 12 October 1918. The rationale behind it being that “If the [German] army succeeds in repulsing the enemy attacks for a little while longer and in losing only little ground, then the conditions laid down for us by the Entente will be less severe than they would be [otherwise].”29

By 9:35 am, the delegates arriving from Berlin had only been in Spa for about an hour and a half. Perhaps Supreme Headquarters did imagine that they and the rest of the group would depart and complete the journey to Guise, on Foch’s designated road, in the two and a half hours left before midday (under the impression evidently that the front lines were still in the vicinity of Guise). In the event, however, the delegates did not leave Spa until midday. (As explained in the French part of this account, for a while the Allies were also expecting the delegates to arrive at midday.)

Midday departure from Spa

In Spa, Secretary of State Erzberger, Ambassador Count Obeurndorf, and General von Winterfeld were joined by Navy Captain Vanselow; but the intended fifth armistice delegate was withdrawn. The four set out for the Front around midday, accompanied by an interpreter, stenographer, secretary, and orderlies, in a convoy of five motor cars.30

At midday, Spa Supreme Headquarters transmitted its second telegram to Senlis to announce that the delegation, headed by Erzberger, had left Spa at midday, that ten persons (plus drivers) were travelling in the group and would reach the French lines between four and five o’clock that afternoon.

Admiral Paul von Hintze informed the Foreign Ministry in Berlin (as its representative at Spa Headquarters) that the Erzberger Delegation left for the Front at twelve noon, that General Erich von Gündell had withdrawn as a delegate, and that a second group of assistants was preparing to follow later.30 Von Hintze had persuaded Erzberger to exclude von Gündell from the group, and both he and the General remained in Spa during the next few days. (Von Hintze and von Gündell were erroneously and confusingly reported in many newspapers to be leading members of what Roy W. Howard called the von Hintze armistice delegation, information about which he believed had been deliberately withheld from the public.)31

Cease-fire at 1:30 pm

In the area around La Capelle, German units from General von Anwarter’s 5th and 11th Infantry Divisions, of General von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army, faced French First Army units there. Presumably therefore, apart from von Hutier, General von Anwarter was among the first to be told during the morning of 7 November that an armistice delegation was heading for his sector.

His headquarters were in the town of Rocquigny, north-east of La Capelle, and by midday preparations were already in hand to provide a suitable bugler to accompany the delegations’ motor cars as they travelled to the French positions. But the General was unsure at midday when the delegation would arrive.32 Nevertheless, he issued orders for a cease-fire to begin at 1:30 pm.33

Thus, by early afternoon on 7 November, the German commander in the La Capelle area had ordered a cease-fire on his side of the front lines in anticipation of the armistice delegates’ arrival, as had the French commander on his side of the lines. However, there was no prior arrangement or communication between them about the move.34

Cease-fire at 3:00 pm

At 12:30 pm, the third Spa telegram to Senlis announced that German forces would stop firing on the Front at three o’clock that afternoon to allow the armistice delegation to cross the lines, and that men would be working to repair the La Capelle road ahead of its vehicles.14 It is not certain whether Spa Supreme Army Headquarters also issued an order specifying that a cease-fire zone should be implemented from German positions along the Étroeungt to Ohis line into French positions; but the zone was in operation from 3:00 pm.

In the light of this development, General von Anwarter’s 1:30 pm cease-fire appears to have been premature by an hour and a half. Of course, it may have been the General’s own decision to order the earlier cease-fire; or he may have received orders that gave him the wrong start-time for the three o’clock cease-fire – ‘1:30 pm’ instead of ‘3:00 pm’. And it is not known whether he had delineated a different cease-fire zone for his 1:30 pm cease-fire.

Whatever the explanation, Anwarter’s troops at some of his forward positions in the La Capelle area announced to the French that an armistice had been signed and that they had been told to cease hostilities at 1:30 pm. (Bourbon-Busset mentioned this matter to General von Winterfeldt when the delegates arrived in La Capelle; the General commented that it must have been a misunderstanding.)35

Long delays

It is not known here whether a particular route from Spa to the crossing-point was marked out for the delegations’ vehicles. But the five hours’ estimated journey-time proved to be insufficient, in the prevailing circumstances of 7 November 1918, and the delegates had to contend with numerous delays. The first, occurring as they were leaving Spa, was caused by a collision that damaged two of their cars (no passengers were injured) and reduced the convoy to three. But the main cause was the damaged roads. Even some distance from shell-damage near the Front, roads became virtually impassable as retreating soldiers blocked them with trees and buried delayed-action mines to obstruct the French advance.

‘White-flag missions’

At his Headquarters in Rocquigny, General von Anwarter received a number of reports about the delegation’s slow progress and about the French not ceasing hostilities and taking prisoners. As a result, in the course of the afternoon he sent two officers, a Lieutenant von Jacobi and a Major von Behr, on separate missions to inform the French of the delegation’s delays and to protest at an apparent absence of a French cease-fire for its safety.

Von Jacobi’s was the first of the two ‘white-flag missions’ to the French lines. He and two German soldiers (all on horseback) met French commanders Lieutenant Hengy and Captain Lhuillier outside La Capelle, and informed them that the armistice delegation was being held up because of the condition of the roads and would not now arrive by 5:00 pm – the arrival-time given in the second Spa-Senlis wireless telegram. He was with Hengy and Lhuillier from about 4:30 pm. Lhuillier allowed one of the German soldiers to leave to report to General von Anwarter what was happening, ahead of von Jacobi’s own eventual return (with his other soldier) to his headquarters sometime after 5:00 pm.

Major von Behr’s ‘white-flag mission’ delivered a letter from General von Anwarter for the French Commander in La Capelle; he arrived by car with two other officers around 7:00 pm. By this time, von Anwarter must have been told that the delegation was now to be expected between 8:00 pm and 10:00 pm – information transmitted at 5:30 pm in the fourth Spa-Senlis telegram (after von Jacobi’s mission).14 By inference, the General instructed von Behr to make sure the French were aware of this and to insist that they prepare for the delegates’ safe arrival: his mission, which occurred within two hours of von Jacobi’s, is more understandable in this context.

Von Behr and his accompanying officers remained at La Capelle to wait for the delegates’ arrival (whether General von Anwarter was made aware of this is not clear). When von Behr spoke to the delegates later that evening, Commander Bourbon-Busset reportedly overheard him telling General von Winterfeldt that it was essential to agree to an armistice because of the poor morale of the German troops.36

Further protests to the French about the cease-fire

When the German 3:00 pm cease-fire came into effect, it applied to their positions facing the French along a line from Étroeungt, north of La Capelle, to Ohis, in the south-east.21 And it extended beyond the northern and southern lines that delimited the French 4:00 pm cease-fire zone which was effective an hour later than the Germans’. (See cease-fire zones sketch map.)

Consequently, after 3:00 pm French troops continued moving forward and into the Étroeungt-Ohis cease-fire zone. General von Hutier, the Eighteenth Army Commander, contacted General Debeney, French First Army Commander, and asked him to withdraw those troops who had moved forward and to bring the French cease-fire zone in line with his. He also requested to be informed ten hours beforehand of any French decision to lift their cease-fire. It is not certain when von Hutier sent this message but Debeney received it at 7:50 pm, so it obviously went out before that. During the two hours and twenty-five minutes before Debeney’s reply was transmitted at 10:15 pm, the armistice delegates finally crossed the French forward positions – safely.26

The delegates’ arrival

At 6:00 pm – after the von Jacobi and before the von Behr ‘white flag missions’ – the delegates reached Chimay. Here the local German commander tried to persuade Erzberger to halt his journey and stay there overnight because of the condition of the roads to the Front and the time it would take to clear them. But Erzberger insisted on continuing. He telephoned the German commander in Trélon (north of the designated road, to the west of Chimay and east of Fourmies) and persuaded him to have the roads cleared so that his vehicles could proceed there from Chimay. Able eventually to move on, the delegates arrived in Trélon around 7:30 pm, presumably not long after von Behr had given von Anwarter’s letter to Bourbon-Busset.

From Trélon they were able to drive back to Foch’s designated road and reached Fourmies by 8:30 pm. Here they were joined by a bugler and acquired three white flags (cut from tablecloths). But instead of following the road directly from there to La Capelle, they headed north-west to Rocquigny and General von Anwarter’s Headquarters. They arrived here by 9:00 pm; and then left in five motor cars for Haudroy and the forward French positions to the south-west, the bugler on the leading car and a white flag attached to each of the first three. Just before 9:20 pm, French soldiers positioned outside La Capelle, around the road leading to Haudroy, spotted the cars’ headlights, heard the bugle, and promptly alerted their officers.37 Where the cars halted on the road was just a short distance outside La Capelle.38

So, more than twenty-eight hours after leaving Berlin, and nearly nine and a half after leaving Spa, the armistice delegates finally crossed the front lines. Nearly twelve hours later, they were taken to Marshal Foch for their first armistice meeting.

Map showing Haudroy on Foch’s designated road between Chimay and Guise, and the delegation’s supposed approach to it after leaving Spa in Belgium.39

Sketch Map: the delegation’s actual route from Chimay to La Capelle (in brown), the cease-fire zones, and crossing-point, x.

Addendum

Some notes made from a 1934 German Newspaper Feature about Events at the Crossing-Point

Marking the sixteenth anniversary of the end of the Great War, the Kolnische Illustrierte Zeitung published an article by a Dr Ernest Overhnes about “important and little-known” events that occurred on 7 November 1918 in the sector where the armistice delegation crossed the front lines.

Arthur Zobrowski, the German bugler who sounded the German cease-fire as the delegates moved from Haudroy to the French positions, and Pierre Sellier the French bugler who replaced him and sounded the French cease-fire as the cars drove on to La Capelle, are the main focus of the article. But mention is also made of arrangements by both sides for halting hostilities around the crossing-point.

Regarding these, Dr Overhnes wrote that a cessation of hostilities in the sector, from three o’clock in the afternoon until midnight, was agreed with the French, by radio, on 7 November. He also remarked that General von Anwarter put a cease-fire in place at midday. (This would have been 11:00 am French time.) But he does not mention a 1:30 pm cease-fire being ordered by the General.

However, according to Overhnes, the French forward positions did not know their own High Command had agreed to a cease-fire, and so continued hostilities well into the afternoon. Consequently, von Anwarter had to send some of his officers (not named) to negotiate with the general commanding the French infantry. The latter told them that he had not received an order to suspend hostilities, but on his own authority ordered a cease-fire in his area – the time was about 6:00 pm.

The article provides little clarification of these or other events it mentions.

[Notes made from Version allemande de l’arrivée devant les lignes françaises de la Mission parlementaire, d’après le journal « Kolnische Illustrierte Zeitung ». Laiss, pp71-77]

© James Smith (March 2018) (Reviewed September 2020; November 2024; With additions April 2025)

MAIN SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Buat, Général Edmond, Journal, 1914-1923. (France, 2015.) Kindle Edition.

Center Of Military History, United States Army, United States Army in the World War, 1917-1919. Volume 10. Part 1. The Armistice Agreement and Related Documents. (Washington, D.C., 1948; 1991) [Available online]

De Gmeline, Patrick, Le 11 Novembre 1918 : La 11e heure du 11e jour du 11e mois. (Presses de la Cité. Paris. 1998)

Ducornez, Auguste, Le 19e Bataillon de Chasseurs à Pied pendant La Guerre 1914-1918. (Berger-Levrault. Paris. No date) [Available online through Gallica.bnf.fr]

Erzberger, Matthias, Souvenirs de Guerre. (Payot. Paris. 1921)

Laiss, Lucien, L’Arrivée des Parlementaires Allemands Devant Le Front Occupé par Le 171me R.I. (B. Arthaud. Grenoble. 1938)

Smith, James, The Spa-Senlis Telegrams and the German Armistice Delegation, 6-7 November 1918. On this website.

Vilain, Charles, Le 7 novembre 1918 à Haudroy. (Saint Quentin. 1968) [First published in 1938 for the twentieth anniversary; republished in 1968 for the fiftieth anniversary.)

Wesserling, mémoires familiales, Stamm, Binder, Armistice – Radiogrammes du 5 au 17 novembre 1918. http://www.wesserling.fr (February 2017)

Weygand, Général Maxime, Le 11 Novembre. (Flammarion. 1932)

NOTES

- a) Buat, 6 novembre 1918; b) Appendix 1 (Spa-Senlis Telegrams); c) United States Army in the World War, Volume 10, Part 1: ‘Fldr. 1: Message: Parliamentaries to be stopped at Front Line. Second Army, A.E.F., November 7, 1918’ ; d) F. L. Huidekoper, The History of the 33rd Division A.E.F., pp193 and 191. (Volume 1 of Illinois in the World War, Illinois, 1921.) e) De Gmeline, pp192-195 and Laiss, pp29-33. f) From the front page of the Daily Express, London, Friday, November 8, 1918. Map shown here with the permission of digital page image copyright holders Reach PLC. (Page image created courtesy of The British Library Board.) g) From the front page of the London Evening News, 7 November 1918. Digital page image and content copyright of The British Library Board. Both newspapers are available from the British Newspaper Archive website.

- Weygand, Chapter II, ‘L’armistice sur le front’, p17. De Gmeline, pp196-197 ; 200.

- De Gmeline, pp200-201.

- Ducornez, p81.

- Laiss, pp34-35 ; de Gmeline, p203

- Laiss, p37.

- Ducornez, pp81-82 ; De Gmeline, p210. Details about the time and location in La Capelle of Ducornez’s initial meeting with Bourbon-Busset differ slightly between these two sources.

- De Gmeline, p212.

- Hew Pike, From the Front Line: Family Letters and Diaries. ‘Thursday 7th November’, p57. (Pen & Sword Military, 2008.) See also “On the German Side of the Crossing Point”, ‘Will reach the front at midday’ in this article.

- Ducornez, p81. De Gmeline, pp212-213.

- Vilain p9 – says the telephone call was at midday.

- De Gmeline, p215. According to some sources, the delegates were blindfolded: “The motor-cars which brought them flew the white flag . . . the papers and identity of the envoys were carefully verified . . . . Their eyes were bandaged and the procession started for their resting place for the night.” From the South Wales Post, Saturday, November 9, 1918, p4, under “BLINDFOLDED. How the Envoys Reached the French Lines.” The information came from “PARIS, Friday”, and seems to be inaccurate.

- See Appendix 1 (Spa-Senlis Telegrams); and Buat, 7 novembre 1918.

- See Appendix 1 (Spa-Senlis Telegrams).

- De Gmeline, pp218-219, notes that the message was received at Senlis and prompted General Weygand to have the armistice railway carriages moved to Rethondes.

- Laiss, pp41-43 ; Ducornez, pp81-82 ; de Gmeline, pp213-215. Laiss does not point out any difference between French and German time, thus giving the impression that 1:30 pm for the start of this German cease-fire was 1:30 pm French time. De Gmeline identifies 1:30 pm as being the German time and converts it to French time. Ducornez does not record that the Germans made known this cease-fire on his side of the lines.

- The figure is based on details contained in De Gmeline, pp213-220.

- Weygand, p18.

- Ducornez, pp81-82. De Gmeline writes, without clarification, that at 1:00 pm Lieutenant Hengy received the order to cease-firing until midnight (p217).

- Buat, 7 novembre 1918 : « [Les Allemands] demandent encore que, sur le front Etroeungt-Ohis, le feu cesse de telle heure à telle heure ? On répond que dans une bande comprenant la route précitée, le feu cessera de midi à 6 heures – le passage des parlementaires étant annoncé entre 2 et 4 heures . . .. Nous portons le délai à minuit . . .. Enfin, comme il y a encore du retard, le délai est prolongé jusqu’à 6 heures du matin du 8 novembre. »

- Wesserling, mémoires familiales, Stamm, Binder. ‘7 novembre 1918 – 15h. Radio passe par le poste météo français “MAX” (région de Noyon) à 15 heures. ORDRE’; and ‘7 novembre 1918 – 18h 30. De “MYZ“ 18 heures 30, à tous les postes : ORDRE’.

- Buat, 7 novembre 1918 : “Ils réclament . . . une suspension d’armes, toujours sur le front indiqué par eux. Réponse : toutes dispositions ont été prises pour la sûreté des parlementaires. »

- De Gmeline states ‘before 5:00 pm’ (p222), which seems to be the German time.

- Laiss, pp41-42 and pp44-45; Vilain, pp10-11; De Gmeline, pp222-224. Laiss and Vilain do not mention that von Jacobi complained to the French about not observing a cessation of hostilities, or that he told them when the delegates might arrive, only that he could not give a precise time because of the damaged roads.

- De Gmeline, pp230-231. The other sources cited in this article do not mention von Behr’s arrival at La Capelle.

- Wesserling, mémoires familiales, Stamm, Binder. ‘7 novembre 1918 – 18h 50. Radiogramme de l’antenne no 4 (18h 50), au général Debeney, Commandant en Chef de l’Armée Francaise’; and ‘7 novembre 1918 – 21h 15. Général commandant d’Armée Debeney à A.O.K. Huter. 21h 15 – Réponse à message reçu à 18h 50’. ‘Huter’ should be ‘Hutier’ – General Oskar von Hutier of the German Eighteenth Army, facing Debeney’s First French Army.

- See Appendix 1 (Spa-Senlis Telegrams); De Gmeline, p235.

- Laiss, p51. Ducornez, p85. De Gmeline, p250. The conversation with von Winterfeld is noted in Vilain, pp17-18; and de Gmeline, p244-245. A slightly different version, according to which Bourbon-Busset spoke to Erzberger, not von Winterfeld, about the matter, is in René Christian-Frogé, La Grande Guerre 1914—1918, Tome Deuxième (Paris 1923), under ‘La Guerre Moderne: Des Parlementaires En Automobile’, p222.

- United States Army in The World War 1917-1919, Volume 10, Part 1: ‘The Armistice Agreement and Related Documents’. ‘HS Ger. File: 810-33.5: Fldr. I: War Diary: Group of Armies Gallwitz. November 7, 1918, p33; Group of Armies Gallwitz. October 12, 1918, p8; Group of Armies Gallwitz. October 28, 1918, p26. The excerpts are from editorial translations of the telegrams. Many German military archives from 1914-1918 were lost during the 1939-1945 War, so the originals probably no longer exist. See: Records lost as a result of war http://www.bundesarchiv.de

- United States Army in the World War 1917-1919, Volume 10, Part 1: ‘Telegram, German Document No. 102 (Editorial Translation). General Headquarters, November 7, 1918, to Imperial Secretary of State, Foreign Office’.

- Erzberger, p376. See the ‘False Armistice Conspiracy Theories’ article on this website.

- De Gmeline, pp215-216.

- Confusingly, on pp216 and 222 de Gmeline gives midday German time as the time the cease-fire started; but on pp213, 215, 231 he gives 1:30 pm German time, which is the time given in this article.

- Nicholas Best, in The Greatest Day in History: How the Great War Really Ended, clearly implies that there was some prior arrangement between the French and Germans. He wrote: “The timetable agreed with the French had already expired, so the commander decided to send some officers forward to negotiate an extension to the ceasefire before Erzberger’s convoy followed on behind”. (p77. London, 2008) The commander referred to here is not von Anwarter, but the one in Trélon who had the roads cleared for Erzberger’s vehicles. Erzberger talks in some detail in his memoirs about his conversation with this commander but does not mention any officers being sent by him to discuss a cease-fire extension with the French.

- De Gmeline, p244. Vilain also notes the conversation (pp17-18). But it is not reported in the other main sources used for this article.

- Weygand, p20 ; de Gmeline, p245.

- Erzberger, pp376-377 and de Gmeline, pp232-234, give the time of arrival in Chimay as “about 6 o’clock” and “18:00 hours” respectively; and the arrival time in Trélon as “about half-past-seven” (Erzberger, p377) and “19h 30” (de Gmeline, pp237-240). Only de Gmeline gives an arrival time in Fourmies, which, having switched to French time, he says was “19 h 30” (p237). The delegation’s two damaged vehicles were obviously replaced somewhere along the route to Rocquigny.

- Illustrations, photographs and maps relating to the delegation’s crossing are available online at Forum Pages 14-18, Le passage du Front par les plénipotentiaires allemands

- The Excelsior newspaper, Saturday 9 November 1918, front page. Available through Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Note : “most of the content available on Gallica consists of digital reproductions of works in the public domain from the BnF collections.”