This article describes Roy Howard’s attempts to find out what caused the False Armistice, and the archived information he collected about it from sundry sources. A companion article relates how Arthur Hornblow, who met Howard in Brest, was given information about the Jackson False Armistice Telegram. Combined, their findings (which they seem not to have shared with each other) mostly concern the 7 November 1918 afternoon false armistice news.

Howard’s search and its results

When Howard left Brest on 10 November 1918, he was “utterly distressed” over the armistice message he had sent to United Press (UP) in New York City three days earlier, according to Fred Cook who saw him on board ship just before his departure. ENDNOTE 1 In the few days it took to cross the Atlantic, Howard would have had time to reflect on what had happened, and he returned firmly convinced that the US authorities were withholding key details from the public concerning the False Armistice. Using UP’s network, he set about trying to unearth the truth behind the misinformation in his armistice cablegram from Brest that embroiled him and his agency in acrimonious controversy and threatened them with ruinous consequences. If he could “get into the facts deeply enough”, he believed he would uncover the “whole story” about the False Armistice which would “round out and throw a new light on the developments of November 7th”. 2 And with this he would demonstrate irrefutably to detractors that he and United Press had not behaved dishonestly, unprofessionally and unscrupulously in their handling of what the New York Times labelled “a monstrous invention” about the end of the war. 3

Letters in his archive show that Howard had some early promising leads. For during the first nine months after the Armistice, he obtained details about four official armistice messages that were actually transmitted, and five that were allegedly transmitted on 7 November 1918.

Of the five alleged messages, two were to the Navy Department from Admiral Wilson in Brest, and two were to the State Department from Special Representative Edward House in Paris. Howard had information about these by early December 1918. The fifth was to the State Department from the American Ambassador in Paris, William Sharp, but it is not certain when Howard first had the information about this one. And it has not been possible to verify the authenticity of any of them.

Of the four official armistice messages whose transmission can be verified, one was from US Navy Headquarters in Paris, sent by a Lieutenant Emmett King, who told a United Press employee about it on 19 December 1918. One was the Jackson armistice message to Admiral H. B. Wilson in Brest which Howard forwarded to New York City and thereby started the 7 November armistice celebrations across North America. Howard already had a pencil-note of this message, given to him in Brest on 7 November, but he came by a copy of the actual telegram-form and message in August 1919. The other two were messages signalled to warships in the British Grand Fleet on 7 November. Howard left copies of these in his archive, without any comments.

The alleged messages from Admiral Wilson to the Navy Department, Edward House to the State Department, and Ambassador Sharp to the State Department.

Not long after his return to the United States, in a confidential letter from New York dated 2 December 1918, Howard revealed the alleged armistice messages from Admiral Wilson and Edward House to Robert (Bob) Bender, his news manager at the UP office in Washington, DC. (Edward House was often referred to as “Colonel House” but he had no official military rank.)

About Admiral Wilson’s, the details were merely that on 7 November the Navy Department received a cablegram at 12:10 pm from him stating “headquarters reports armistice signed”; and a follow-on at 1:10 pm reading “headquarters report error in signature”. About Edward House’s, they were that the State Department had a cablegram at 12:30 pm from him stating “armistice signed congratulations”; but at 12:40 pm, just ten minutes later, another one warning that there had been an error and promising to send a “full report”.

“Of course”, Howard asserted, Josephus Daniels (Navy Secretary) and Frank Polk (State Department Counsellor) know “all about these messages”, which, he explained, had come “in a round-about way” from a person “unknown” to him and “whose acquaintance [he] deliberately avoided making”. 2 (Whoever he was, the unnamed informant must have been an insider or someone with insider-contacts in Washington, DC.) Many years later, Howard disclosed to an American journalist that Ambassador William Sharp had also cabled a false armistice message to the State Department on 7 November 1918 which was “virtually identical to the one received by Admiral Wilson” (meaning, the Jackson armistice message). 4

Howard may already have acquired these supposed Wilson and House messages before a meeting he had with Josephus Daniels at the Navy Department in late November 1918. If he had, it is assumed that he asked Daniels about them.

Unhelpful meeting with Josephus Daniels (19 November 1918)

Howard wanted to see Daniels (in private life, a newspaper proprietor and Associated Press (AP) subscriber) ostensibly “to express his appreciation” for Admiral Wilson’s statement exonerating him and United Press from blame for the false armistice misinformation. FTNT? But it is more likely that his main purpose was to question Daniels about the Jackson Armistice Telegram to Wilson, the alleged messages Wilson sent to Daniels on 7 November (if he already had them), and other False Armistice events.

A few days after the meeting, Daniels confided to an AP Press Superintendent something of what had occurred and of his annoyance at Howard’s attitude:

“Howard came here with the statement which Admiral Wilson had given him, and I told him that it did not lessen his responsibility a bit. I said to Howard ‘you fell down, you are in the hole. Admiral Wilson fell down in saying anything to you at all and you fell down to a pretty (sic) when you transmitted what he said as a flat statement. The best thing you can do about it is to shut up and let the newspapers and the American people forget about it if they can.’ 5

Not the response that Howard was presumably hoping for or expecting. The next day – 20 November – Howard made a statement to the press in which he referred to the meeting with Daniels and remarked that:

“Upon my return to the United States I learned that no news had been published here of the fact that celebrations of the signing of the armistice took place on Nov. 7 at practically all the army and naval bases on the French coast.

I was also surprised to learn that nothing had reached here by cable concerning the fact that all Paris had the report of the armistice being signed. At the American Luncheon Club meeting in Paris on that day the toastmaster arose, and, with Admiral Benson seated on one side of him and American Consul General [Thackara] on the other announced on what he said was the authority of the American Embassy that the armistice had been signed. All the celebration on that day was by no means on this side of the Atlantic.

Nothing much has yet been said as to the source of Admiral Wilson’s information. This is not for me to discuss. Nothing has been said as to the reason for the report current on that day throughout France. No explanation has yet been offered of how the report reached the American Embassy in Paris as official. Neither has any explanation been offered yet as to what became of the first German armistice delegation, headed by von Hintze, which was reported to have reached the French lines on Nov. 6 and which then disappeared from the news, being supplanted by the Erzberger plenipotentiaries.” 3

No doubt hoping to stimulate popular interest and demand for answers, Howard obviously chose not to “shut up” about the False Armistice and let the matter rest. The only comment Secretary Daniels was prepared to give was that he “authorized no statement of Howard’s conference with me: in fact, I did not understand he intended to make any.” 3

Unsuccessful approaches to Admiral Wilson for a meeting

Howard wrote a number of times to Admiral Wilson after the Armistice, hoping to meet him again to talk about “the somewhat memorable incident of November 7th last in which you and I appeared as co-stars” – noting that information about its “interesting phases” had recently come to his attention. 6 But most of his letters were ignored; Wilson refused to have anything more to do with Howard after their meetings in Brest of 7-8 November 1918. 7

Information Howard Subsequently Obtained

Despite these initial setbacks, Howard was determined to persevere. He told Bob Bender, in his 2 December 1918 communication, he wanted the Navy Department’s affirmation that the armistice announcement to Admiral Wilson came “officially from [Navy] Headquarters [in Paris]” and that Wilson had duly reported it to them. And Edward House’s that he or an aide “actually filed the same [false] news” on 7 November to either the State Department or President Woodrow Wilson. He was also hoping to learn what the “error” was that Admiral Wilson and House referred to in their follow-on cablegrams (above), where Navy Headquarters in Paris “got their report in the first place”, what originally gave rise to the report, and what became of the German delegates Howard believed had crossed the Allied lines on Wednesday 6 November with authority to sign an armistice (the delegates he alluded to in his press statement following his meeting with Daniels a few days earlier). And he confided that he had now decided to approach President Wilson and Edward House themselves for the answers. He felt they would be more understanding and ready, for party-political reasons, to give him details that would put a stop to insults against him and United Press about their handling of the false armistice message. 2

Howard told Bender not to mention the contents of his 2 December 1918 letter “to a soul in Washington”; it was “necessarily confidential” for the time being.

“I think that this can better be done in Paris”

The Peace Conference between the Allies and defeated Central Powers, which drew up the treaties that formally ended the Great War, was due to open in Paris (at Versailles) on 18 January 1919. Edward House was already in Paris; President Wilson would soon be travelling there for the Conference. And Howard proposed to make use of the occasion to ask them about the False Armistice.

Bob Bender was one of the United Press team preparing to cover the Conference. Also in the team were Fred S. Ferguson, UP’s chief war correspondent in France, William Philip Simms, manager of the agency’s Paris Office, and Ed Keen, manager of the London Office. 8

Howard instructed Bender to show the 2 December letter to the others when they met in Paris. He wanted them all to assist in gathering information from US officials there – “I would like that all four of you keep your ears open for any clues or any information that may be obtainable bearing on the real reason for the [armistice] report of November 7th”. When he was back in Paris to oversee UP’s coverage, Howard planned to “take this matter up with House personally”; but if anything arose to prevent this, Fred Ferguson was to assume responsibility for meeting House. 2

As well as being manager of UP’s Washington Office (since 1917) Bob Bender was also the agency’s “regular White House correspondent”. 9 He had been assigned to President Wilson’s press entourage and, as he was due to travel to France on the President’s ship, Howard thought that an opportunity might arise during the voyage for Bender to “take [the] matter up with the President directly”. He urged him to do so “if such a contingency should arise”. 2

Howard reasoned at some length why President Wilson and House might prove to be amenable:

“In view of the fact that all of our troubles were occasioned by information furnished us through American government channels, in further view of the fact that the American government in Washington was a recipient of the very same information that we received – received it from its most trusted representative abroad Colonel House – and in further view of the fact that our misfortune was intensified and complicated by the action of the Navy Department in holding up our correction, there seems to me to be good reason why the American government itself should willingly and quickly take whatever action is necessary to restore to us any standing or prestige that we may have lost by reason of handling information secured through the government agents.” 10

Alluding to UP’s support for the Democratic Party and Wilson’s Administration, he added that it was “to [the President’s] interest that an organization such as United Press should not be discredited in the public mind. The President is acquainted with the Associated Press and will be able to understand the unfair advantage they have of this incident in an attempt to belittle our standing and our reliability”.

Howard considered it “vitally important”to obtain the information quickly and “to have this thing sprung as a full fledged [sic] story with all the punch and carrying force that can be put into it” rather than have “the facts dribble out a bit at a time [with no] corrective effect. Therefore, the quicker this matter is cleaned up the better for us”.

However, he appreciated that things must be done “without embarrassing the American position” and, suspecting this might not be possible, he decided that should Edward House intimate that he could not “clear it up at this time without embarrassing the government” then they would have to wait until it could be told “without damaging the interests of the government”. In this event, United Press would just have to “stand the gaff a little longer”. 2

President Wilson left for France on 4 December 1918 on board the SSGeorge Washington, as presumably did Bob Bender with Howard’s confidential 2 December letter. The ship docked in Brest on 13 December; the President and his party were in Paris the following day. Howard was due to leave for France on 14 December but seems to have postponed his departure until after Christmas; whether he eventually travelled to Paris for the Peace Conference is not certain from readily available sources. 11

In Paris

During the Conference, Fred Ferguson (from UP’s Paris office) managed to gain an illicit exclusive pre-publication access to the text of Article Ten of the Treaty of Versailles. This is part of the Covenant of the League of Nations and guaranteed the territorial integrity and political independence of all League Member-States. Ferguson had tried in vain to obtain information about this from Edward House, but succeeded with someone he knew “who was a minor official of the delegation”. Apparently, the latter arranged for Ferguson to see the document clandestinely in a room of the Crillon Hotel in Paris, where American officials were staying during the Peace Conference.12

However, whether Ferguson, Bender, Simms, Keen, or Howard (if he was there) managed to secure any confidential information about 7 November 1918 is not known. And whatever may have transpired in Paris, neither Howard’s papers nor his later writings suggest that he was able to resolve the False Armistice mystery and use the knowledge to rehabilitate his and UP’s standing and reputation. Perhaps attempts to engage President Wilson, Edward House, and other officials about the alleged false armistice telegrams were rebuffed. Or perhaps information was actually provided, but on condition that it would remain strictly “off the record” because the whole affair could not be cleared up “at this time without embarrassing the government” – as Howard (in his letter to Bob Bender before the Conference) suggested might happen.

President Wilson returned to the United States in the middle of February 1919 (almost a year before the Conference ended in January 1920), Edward House in October 1919. Howard wrote to the latter welcoming him back to New York, but it is not certain whether they met that year or indeed ever discussed the False Armistice. 13

Meanwhile, from Paris Howard had obtained a few more False Armistice snippets before the end of December 1918. These are in a letter Navy Lieutenant Emmett King sent to “W. F. L.” from US Navy Headquarters in Paris. It was copied and presumably forwarded to Howard by “W. F. L.” – William F. Lynch, described in 1916 as being UP’s “Chief Operator” (of Telegraph). 14

“It is too bad that the whole case cannot be put before the public” (19 December 1918)

Emmett King described himself as the Navy Headquarters’ “Chief Electrician, (Radio)” and apparently knew W. F .L. – perhaps through their work in radio telegraphy. 15 The letter may be a reply to one mentioning events in the USA on 7 November that W. F. L. had already written to him, but the impression is that King wrote it without any prompting. He had, he explained, read some American papers’ reports on the False Armistice and the “strong criticism” levelled against United Press by Associated Press and other agencies, and wanted W. F. L. to know that United Press had “pulled the biggest ‘beat’ of all time” with its armistice bulletin.

He claimed to know “what caused the whole affair”, and though he said he was not at liberty “just at present [to] explain it”, nevertheless offered these tidbits:

“About 3:50 p.m., the seventh [of November] a message was handed me, in plain English, reading identically the same as the message that was afterwards published in America to the effect that hostilities had ceased. I flashed the message and as soon as had finished it was taken from my hands and never returned to the files. I can assure you that the signature on the message was thoroughly official and that the message itself was absolutely from official channels, so much so, that in half an hours time [sic] the entire Atlantic fleet would have been on its way into port, but they stopped the proceedings before they got too far . . . . But rest assured of this fact: That the United Press had the right dope and had in reality pulled the biggest ‘beat’ of all time. I know this for I handled the whole case. The whole ‘bone’ [‘stupid mistake’] lay in a government official (not American). It is too bad that the whole case cannot be put before the public . . . what a shame that [they] don’t know the facts.”

Having been working on the Armistice and “later peace stuff”, King explained that he was now engaged “in handling all Colonel House’s work”. 16 And, assuming that Howard was in Paris in December 1918, hoped he might “drop around” to see him and find out “what he knows regarding that message”. 17

King did not say who handed the armistice message to him, where it had come from, or where and to whom he sent it; but what he sent was the Jackson armistice message of 7 November 1918. He was the operator who actually wired it from Paris to Admiral Wilson in Brest. 18 He may also have cabled it separately to US Navy Headquarters in London, for his comment that, having “flashed” the message, he was sure “the entire Atlantic fleet would have been on its way into port” had “they” not “stopped the proceedings before they got too far”, implies that the US Atlantic Fleet would have had the message quite quickly. (He did not say whether he had sent a follow-on cancel-message.)

(In November 1918, Admiral Henry T. Mayo was commander of the US Atlantic Fleet; under him, Vice Admiral William S. Sims was in charge of US naval operations in European waters and of US Navy Headquarters in London, which were located in Grosvenor Gardens just a short distance from the American Embassy. Jackson’s message certainly reached the US Navy Headquarters and Embassy in London; and British papers circulated the peace news, which somehow found its way to the British Grand Fleet. 19)

King’s allegation that “a government official (not American)” was responsible for the misinformation suggests that the culprit was French or British. And his comment that the “whole case cannot be put before the public” implies that the Allies were withholding information about what had actually happened – the most obvious reason being that they were trying to prevent any one of them being singled out for blame.

It is not certain when Roy Howard received King’s letter, where he was at the time or whether he or one of his Peace Conference team was able to make use of it. (How long Howard’s team remained in Paris is unclear.) But in view of King’s evident willingness to discuss the 7 November armistice message, the likelihood is that someone did see him in Paris to talk about it. And Howard must have realised it was the Jackson armistice message that King had transmitted. A few months later, a copy of this on its telegram form was acquired for Howard.

A typed-out copy of the Jackson Armistice Telegram (July-August 1919)

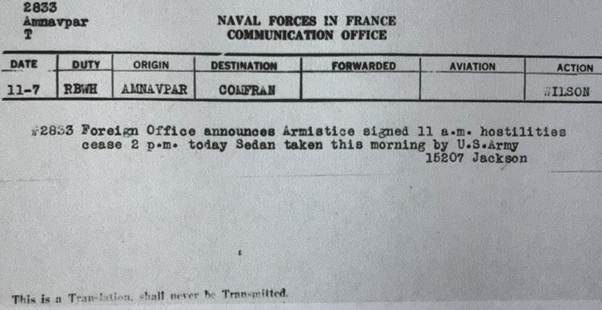

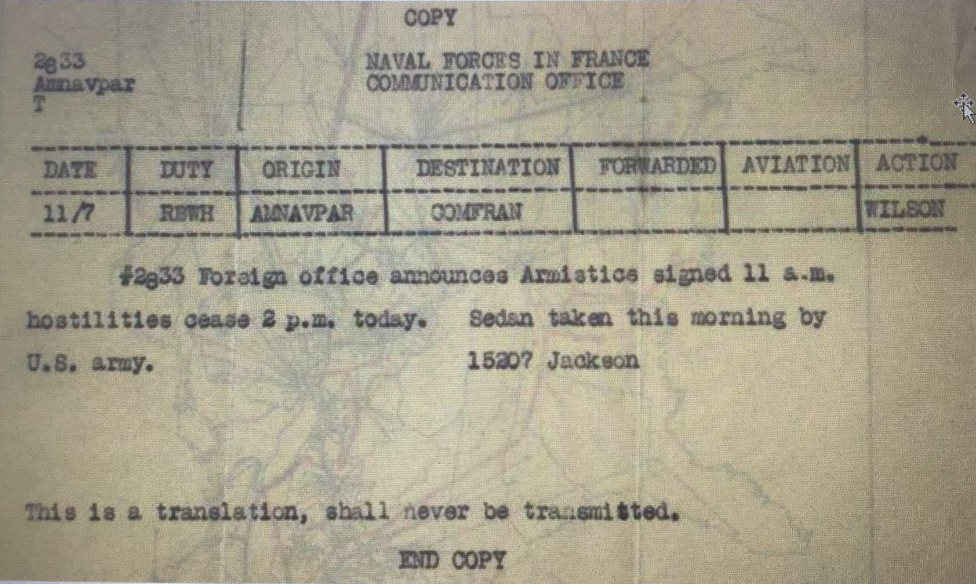

Captain Richard H. Jackson became US Naval Attaché in Paris in May 1918. As such, his instructions were to “confer” with the “Senior Naval Officer afloat in French Waters”. 20 In November 1918 this was Admiral H. B. Wilson whose headquarters were in Brest. During the afternoon of 7 November a bulletin from Paris to Admiral Wilson, carrying Jackson’s name as authorization, announced that an armistice was signed with Germany at 11 o’clock that morning, hostilities had ceased at 2 o’clock that afternoon, and the US Army had taken Sedan in the morning. The Admiral released the news in Brest and gave it to Roy Howard who, purely by chance, had just turned up at his headquarters. 7

The Hugh Baillie letter about the telegram.

On 19 July 1919, Hugh Baillie, UP’s news manager in Washington, DC, sent this information to Howard at United Press in New York City (Howard may have been in New York City or Paris at the time):

“Joyce O’Hara called today. He said a lawyer by the name of Carey, with offices in the Wilkins Building here, was in possession of the original telegram which was sent by Captain (now Admiral) Jackson at the American embassy in Paris to Vice Admiral Wilson, November 7, notifying him the armistice had been signed. O’Hara said Carey formerly was Wilson’s secretary, hence his possession of the telegram. He also said Carey was prepared to state that Captain Jackson got his information of the signing from the French Foreign Office.

O’Hara said Carey was not mercenary, but that he would expect some cash for the telegram.

I told O’Hara I would report what he said to you, and we let it go at that.” 21

(Information about Joyce O’Hara has not been found. There is a “Lieutenant J. A. Carey, (j. g.) Supply Corps, U.S.N.R.F.”, identified as “Flag Secretary” and “Navy Press Censor” at US Navy Headquarters in Brest in November 1918. And the 1919 US Navy Register lists a “Lieutenant (j. g.) Joseph A. Carey (Pay Corps) U.S.N.R.F., who was presumably the same person. 22)

Carey’s allegedly “original” Jackson Armistice Telegram would have looked like this one in the US Naval History and Heritage Command Archive (NHHC) 23:

However, there is no other correspondence in Howard’s archive from Hugh Baillie concerning the telegram, or reply from Howard to Baillie about it. And what became of this alleged “original” is unknown. Perhaps Carey sold it to someone else.

The L. B. Mickel letter about the telegram.

There is another letter in Howard’s archive about the Jackson Armistice Telegram, dated just over three weeks later than Baillie’s. It is from L. B. Mickel, who eventually became United Press Superintendent of U.S. Bureaus, but was a UP staff-member in Oklahoma City at the time. There are also what seem to be two carbon-copies of it, with annotations respectively of “cc. KAB” and “cc. W.W.H.” hand-written and circled in ink. (“KAB” are the initials of Karl August Bickel, who became President of United Press after Howard; “WWH” those of William W. Hawkins, United Press First Vice President.)

The contents – a brief explanation and a typed-out copy of the Jackson Armistice Telegram – fill a single sheet of “United Press Associations” headed paper:

“Oklahoma City, Okla. Aug 11, 1919.

My Dear Howard:

Here is a copy of the Wilson armistice message on which the admiral based his announcement. It was taken by M. R. Toomer, Oklahoma News staff, from a copy made by a wireless operator in Wilson’s office at Brest. The original is in Wilson’s file. Whether or not it contains new information for you I do not know. To me the ‘Foreign Office announces’ part is new stuff.“ 24 (My italics.)

(Before he read this, Roy Howard was probably unaware that the French Foreign Ministry sent the afternoon false armistice news to the American Embassy – it was most likely “new stuff” to him in August 1919 as much as it was to Mickel.)

Like Baillie’s communication, this is the only one from Mickel in Howard’s archive about the Jackson Armistice Telegram; so there is no explanation as to how the unnamed operator’s “copy” of the “original . . . in Wilson’s file” came to his notice and how it happened to be in Oklahoma City (with or without the operator himself). Nor does Mickel say whether he had to pay for M. R. Toomer to be allowed to take a copy of the “copy” of the “original”.

Whether there was some link between the two letters is unclear. But it seems to be more than coincidental that Mickel’s letter arrived after Baillie’s and the ensuing silence about Carey’s “original”, which is now dismissed as such by implication. A plausible explanation is that J. A. Carey’s and the operator’s “copy” were both duplicates of the Jackson Armistice Telegram. In other words, they were virtually identical to the one said to be in Wilson’s file: genuine Brest US Navy Headquarters telegram-forms filled in with the Jackson armistice message and details wired from US Navy Headquarters in Paris. They would have been in the United States not long before Baillie and Mickel wrote their letters to Howard, because Carey (and perhaps the wireless operator) had evidently been demobilised before July 1919. Indeed, Admiral Wilson left France in February 1919 to take up duties with the US Atlantic Fleet and his headquarters in Brest ceased operations in September.

The Jackson Armistice Telegram in the US Naval History and Heritage Command Archive is presumably the one that was in the Admiral’s file, having been packed up with other official documents and shipped to the United States. From what Baillie and Mickel wrote, it could be inferred that what Mickel secured for Roy Howard in August 1919 was a typed-out copy of either Carey’s or the Brest operator’s duplicates, if there were indeed two of them.

However, how many duplicates may have been made and still exist is not known – it may well be that Carey’s was the only one. The writer is aware that in the United States there is one which has been in private possession for more than two generations, and is almost identical to the image of the Jackson Armistice Telegram in the Naval History and Heritage Command Archive.

Two false armistice messages signalled to the British Fleet

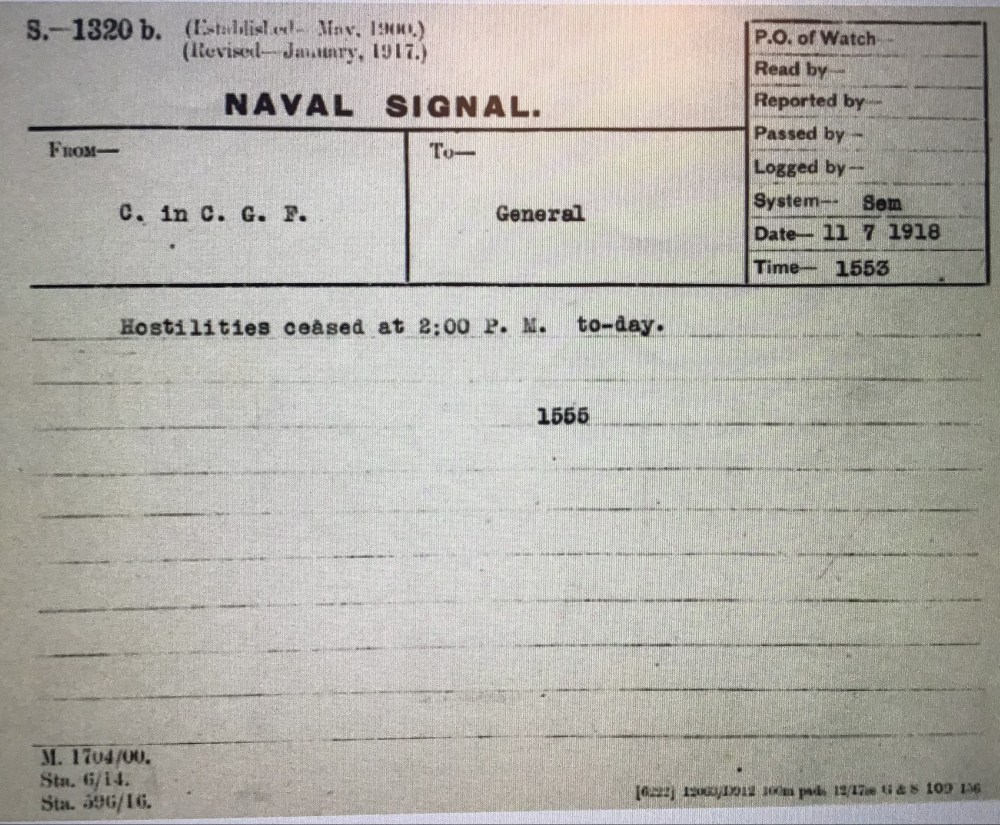

Included in a collection of telegrams from Howard’s four days in Brest are two British Royal Navy signal sheets recording armistice messages sent to warships on 7 November 1918. While there is at least some information about how Howard acquired the other documents discussed here, there are no clues to suggest from whom, when or how Howard came by these naval signals.

This is the first one 26:

Clarifications:

“C. in C. G. F.” is an abbreviation of ‘Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet’.

(The British Grand Fleet was mostly deployed in the North Sea to blockade Germany. Its main bases were at Rosyth, in the Firth of Forth on the east coast of Scotland, and Scapa Flow in the Scottish Orkney Islands. In November 1918, its Commander-in-Chief was Admiral David Beatty.)

“General” – presumably ‘for general release’ to other warships.

“System- Sem”: ‘Sem’ is an abbreviation for ‘semaphore’, indicating that the message “Hostilities ceased at 2:00 P.M. to-day” was sent, in this instance, by semaphore (using either signal-lamps, flags, or mechanical semaphore arms) rather than by wireless transmission.

“Date- 11 7 1918”: that is, November 7 1918.

(This ‘month-day-year’ is the American style of writing the date. The British style is ‘day-month-year’, which would make it ‘7 11 1918’.)

“Time- 1553”: that is, 3:53 pm, indicating the time the message was received. .

“1555”: that is 3:55 pm, indicating the message’s ‘time-of-origin’ – the time it was ordered, which may not be the time it was actually sent out.

(There is obviously an error in these times – as it stands, the message was received by semaphore two minutes before it was ordered to be sent.)

And the second one 27:

Clarifications:

“Lion” denotes the British warship HMS Lion.

(HMS Lion was the flagship of the British Grand Fleet’s battlecruiser force, under Vice Admiral Sir William Pakenham. In November 1918, the ship was at Rosyth, as was Admiral Beatty’s flagship HMS Queen Elizabeth.)

“System – S. L.”: meaning by signal-lamp.

“Time- 1655”: that is, 4:55 pm, when the message “Cancel signal re hostilities ceasing” was received.

“1650”: that is, 4:50 pm, indicating the message’s ‘time-of-origin’.

(With the two signal sheets are what appear to be photographic negatives of them.28)

From these signals, therefore, it seems that around four o’clock on 7 November 1918 a message from Admiral Beatty was sent to warships in the Grand Fleet stating that hostilities had ceased at two o’clock that same afternoon (about two hours earlier), with the implication that the fighting against Germany had ended. There was, however, no mention of an armistice with Germany or specific instruction for the Grand Fleet to cease hostilities. About an hour later, around five o’clock, the cancellation of the ‘hostilities ceased’ message was sent without explanation.

The American date-format indicates that the Royal Navy sheets were being used on a US warship. Indeed, as was publicised after December 1917, US warships were operating with British warships in the North Sea: commanded by Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, Battleship Division Nine of the US Navy’s Atlantic Fleet had joined the Grand Fleet to become the latter’s Sixth Battle Squadron, which in November 1918 consisted of the USS Arkansas, Florida, New York, Texas, and Wyoming. 29 The ships assimilated by adopting the Grand Fleet’s “signals and methods of communication, their plans, policies, manoeuvres and tactics”. 30

During the afternoon of 7 November, the squadron, “without Texas”, left Rosyth at “1308” (1:08 pm) and was away until “4.55” pm (1655). USS Texas, like HMS Lion, remained at Rosyth the whole day. 31 So, while the Sixth Battle Squadron was at sea the “hostilities ceased at 2:00 P.M. today” signal went out just before 4:00 pm; and the “cancel signal re hostilities ceasing” order at practically the same time as the squadron returned to Rosyth.

(See the Addendum below for comments and further information.)

The results of Howard’s search for false armistice information

Based on what he saved in his archive, Roy Howard’s search for the truth about the False Armistice amounted to the two British Navy signal sheets, the typed-out copy of the Jackson Armistice Telegram (rather than the original which Hugh Baillie had told him was for sale), the alleged claims about armistice cablegrams sent from France on 7 November by Admiral Wilson in Brest, Edward House and Ambassador Sharp in Paris, and Lieutenant Emmett King’s disclosure that he transmitted the Jackson armistice message from US Navy Headquarters in Paris.

From these, just one detail crops up in his 1936 ‘Premature Armistice’ chapter for Webb Miller’s book: the “new stuff” L. B. Mickel remarked on in the Jackson Armistice message – namely, that the French Foreign Office ‘announced’ the 7 November False Armistice. Howard used it to claim that a German secret agent in Paris on 7 November 1918 had fooled a secretary at the American Embassy into believing he was telephoning from the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d’Orsay. 32

There may have been other information which Howard did not wish to leave in his archive. But what he made available leaves unanswered the most fundamental of the False Armistice questions Howard outlined to Bob Bender: where the armistice report originally came from (before the French Foreign Office announced it), and what had caused it. The two conspiracy theories Howard offered readers in his 1936 memoir were his way of addressing these. One of them, his own apparently, postulated a German delegation led by Admiral Paul von Hintze and an actual armistice-signing with Marshal Foch on Wednesday 6 November. He eventually discarded this, he said, in favour of his German secret agent theory. In essence, this was the same theory Arthur Hornblow had aired in his 1921 ‘Amazing Armistice’, where he stated that the spy claimed to be forwarding the peace news from the French War Ministry (not the Foreign Ministry). 33

Addendum

Comments and further information about the signals to the British fleet

The following extract is from a piece in an American paper – the New Britain Daily Herald – marking the first anniversary of the False Armistice in the USA. It is regarded here as corroboration that the two armistice signals were actually sent to ships in the British Grand Fleet on 7 November 1918:

“Where the [false armistice] rumor started will always be a mystery. At the time of the circulation of the report, the writer happened to be at sea with the British Fleet. At some time in the forenoon a radio signal was received from the flagship of the fleet H. M. S. Lion, which in effect read, ‘Cease hostilities at 2:00 o’clock’ and which was signed by a British naval staff officer. There could be but one construction to place on this, and that was that Germany had capitulated. The officers upon the ship were discussing the message, copies of which had been posted in various messes, and debating whether they should open fire upon possible submarines after 2 o’clock, when the question was quickly settled for them by another message cancelling the previous one. The armistice had not been signed, although the two messages are proof that the Admiralty, for a very brief time, thought that it had. The rumor and the cancellation came very close together, so close that, the newspaper men who had taken occasion to check up were disappointed almost at once.” 34 (The times on the signal sheets do not support the writer’s observations that the messages “came very close together” or that they were sent in the “forenoon” – they were afternoon messages.)

The New Britain Daily Herald was an Associated Press member at the time and did not publish the armistice misinformation on 7 November 1918. It is not certain who wrote the anniversary item, but it was most likely the work of Lewis Ransome Freeman, an American “magazine and book writer” who had the rank of lieutenant in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and “served . . . for the last twelve months of the War in the Grand Fleet”. 35

The 2:00 pm cessation-of-hostilities detail was most likely from the Jackson armistice message, but evidence as to who actually ordered it to be signalled to the Grand Fleet, and what led up to its cancellation seems to be unavailable. The British Admiralty in London usually provided the Fleet with military intelligence passed on to them or acquired from their own sources – such as wireless telegraph intercepts by the Fleet itself and naval intercept stations around Britain. 36 So it seems highly improbable that any news about the end of the war would have gone to the Fleet without authorization from the Admiralty.

However, a search of the British Admiralty records found nothing relating to a 2:00 pm cessation of hostilities on 7 November that may have been from the Admiralty to Admiral Beatty as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the Grand Fleet. And what was sent to him on Thursday 7 November left no room for assumption that a cessation of hostilities linked to a German armistice might be imminent.

Thus:

Telegram 151 from Beatty himself to the Admiralty, showing the time “1034” (10:34 am) on 7 November, contains the message “Newspapers state German Delegates have crossed Allied lines to negotiate armistice. Request to be informed if this is correct as Grand Fleet should be concentrated at such a critical moment.” (During the evening of Wednesday 6 November and the morning of the 7th, some British papers reported that the German armistice delegates were already at the Front. 37)

The Admiralty’s reply, telegram 220, carries the time “1419” (2:19 pm), over three hours later. Its message: “Immediate. Personal from D.C.N.S. only information in England is that Germany has asked for a rendezvous for Parliamentaires [armistice delegates] and has been given one. They are expected to meet representatives of Marshal Foch at 1700 [5:00 pm] this afternoon Thursday at front line on La Capelle–Guise Road. ends.”

(D.C.N.S. = Deputy Chief of Naval Staff. The information in this reply was derived from the first three Spa-Senlis Telegrams exchanged up to early morning on 7 November. 38)

If (as its “Immediate” command implies) this message left straight away, the C-in-C would therefore have been aware after 2:19 pm – well before the time on the first armistice signal sheet – that the German delegation was still on its way to the Western Front, and that no armistice agreement could be expected on 7 November before 5:00 pm. Later that afternoon (“1657”, 4:57 pm), there was further unambiguous information in telegram 225: “Immediate. Personal from D.C.N.S. Terms of German Armistice provide for reply from Germany being given within 72 hours of terms being handed over. Penalty is withdrawal of terms. This is best guidance we can give you as to period of tension.”

(A telegram to the C-in-C on Friday 8 November reporting the German delegates’ first meeting with Marshal Foch that day, noted that they had requested an armistice and an immediate cessation of hostilities, and that Foch refused the latter.) 39

To put the two signals in context, around the same time that the first one (from the C-in-C) went out at 3:55 pm, Emmett King transmitted the Jackson armistice message to Brest – as he recalled, at “about 3:50 pm”, some thirty minutes later than the Jackson message’s origin-time of 3:20 pm. It is not known where Admiral Beatty actually was at this time. But assuming he was at Rosyth, he would presumably have seen sometime before 3:55 pm the 2:19 pm “immediate” from the Admiralty telling him that the German armistice delegation was still on its way and expected at the Front around 5:00 pm. The second signal (from HMS Lion), about sixty minutes later, has the origin-time 4:50 pm printed on it. This is at least forty-five minutes after the armistice news circulating in Britain was cancelled. And just seven minutes before the Admiralty sent its 225 (4:57 pm) informing Beatty that the Germans would have to accept the armistice terms within seventy-two hours of receiving them.

Surviving from the time of these events are a diary kept by a telegraphist aboard HMS Lion; a number of letters sent home by an officer from the same ship; and diaries kept by an officer of HMS Indomitable, like Lion, deployed in the Grand Fleet’s battlecruiser force. There are entries in them about the 11 November Armistice and its celebration by ships in the Fleet, and about the arrival shortly afterwards of German admirals to make arrangements for the surrender and movement of their warships to the naval base at Scapa Flow. However, they say nothing about Fleet signals on 7 November announcing a 2:00 pm cessation of hostilities. 40

On the other hand, the Sun newspaper in New York City, referring briefly to the uncertainty surrounding the origins of the False Armistice, commented two days after the event that “Talk was heard along Park Row of the possibility of the American warships having picked up a lie sent broadcast by the Nauen wireless in Germany. But this was pure guessing.” 41 In other words, speculation among Park Row newsmen was that US warships had intercepted German 7 November disinformation.

(Park Row, in New York City, was the location of the US daily newspaper industry at that time. The Nauen wireless station, north-west of Berlin, was Germany’s long-range transmitter from where the Spa messages about the German armistice delegation were broadcast for Marshal Foch’s headquarters at Senlis to pick up.)

By and large, the most plausible explanation is the assertion by the New Britain Daily Herald journalist that “the Admiralty, for a very brief time, thought that [the armistice] had [been signed]”. Roy Howard’s copies of the signal sheets are evidence of this. For some reason, however, there is no such evidence in the Admiralty’s own historical records. Perhaps post-war, the two sheets were “considered unimportant” and consequently “removed and destroyed” along with other papers. 42 Or perhaps they were considered a mistake much too embarrassing to be recorded in the official archives.

© James Smith. (Periodically reviewed and edited, August 2019 to February 2026)

REFERENCES

ARCHIVE SOURCES

1. Library of Congress Chronicling America. (Online)

2. Roy Howard Papers. (1892-1964). MSA 1. The Media School Archive, Indiana University Libraries. Bloomington, Indiana.

3. Associated Press Corporate Archives, New York, New York.

4. Admiral H. B. Wilson Papers. Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), Washington, D.C.

5. Edward Mandell House Papers. Yale Library Collections.

6. The (UK) National Archives. Kew, Richmond, TW9 4DU, United Kingdom.

7. The National Maritime Museum. Greenwich, London.

8. East Riding of Yorkshire Archives and Local Studies Service. Champney Road, Beverley, Kingston upon Hull, HU17 8HE.

9. The Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge.

ENDNOTES

1. Article in the Evening Star [Washington, DC] November 11, 1925, p4, under ‘Real “False Armistice” Story Is Now Told By Eyewitness’. (Library of Congress Chronicling America)

2. Roy Howard to Robert J. Bender [UP General News Manager in Washington, DC] CONFIDENTIAL, New York, December 2, 1918. AND Roy Howard to Fred C. Cook, November twenty-eighth 1925, p3. (Roy Howard Papers)

3. The New York Times, 21 November 1918, under ‘Howard Excuses False Peace Report’. Available to subscribers.

4. R. W. Howard to David Lawrence, November 30, 1951. (The letter concerns a remark President Truman made during a Korean War press conference about Howard’s “fake” armistice cablegram.) Quoted by Lawrence in his article ‘Roy Howard Recounts ’18 Story’ for the Evening Star [Washington, DC], December 8, 1951, p13. (Library of Congress Chronicling America) (These alleged messages are discussed in their 7 November 1918 context in ‘False Armistice Cablegrams from France’ on this website.)

5. Letter: L. C. Probert to Frederick Roy Martin, November 21, 1918. AP02A.03A, Subject Files, Box 27, Folder 6. (Associated Press Corporate Archives)

(See the Associated Press suspicions about Admiral Wilson, 8-21 November 1918 aspect of ‘Admiral H. B. Wilson and Roy Howard’s Armistice Cablegram’ on this website.

6. Roy Howard to Admiral Wilson, July 18, 1919. Box 1. (Admiral H. B. Wilson Papers)

7. See the following on this website: ‘Admiral H. B. Wilson and Roy Howard’s Armistice Cablegram’; ‘Arthur Hornblow’s Information about the Jackson Armistice Telegram’; and ‘Roy W. Howard in Brest’, Parts One and Two.

8. See the Fourth Estate, December 7, 1918, p8, under ‘Howard and Keen In Charge of U.P. Staff’, for an item about United Press personnel in their Peace Conference team. Available online through the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

9. J. A. Morris, Deadline Every Minute. The Story of the United Press, pp82, 115. (New York 1957) “[Bender] quickly made friends in the right places and was able to develop a number of exclusive stories, possibly due in part to the fact that he was one of the few Washington reporters who owned an automobile and frequently taxied Joseph Tumulty, the President’s secretary, to his home at the end of the workday.” (p82)

10. For a discussion of Howard’s story about his “warning” cablegram, see Addendum in ‘Roy W. Howard in Brest, Part Two’ on this website.

11. In Roy W. Howard to Fred C. Cook, December 11, 1918. Howard told Cook “I had expected to sail for France on the 14th but a crush of local affairs has made it necessary for me to postpone my trip until after the holidays.” (Roy Howard Papers) In Howard’s Papers only two documents are listed for the whole of 1919, neither being to or from Paris.

12. J. A. Morris, Deadline Every Minute, p116. (Note 9)

13. Among Edward House’s papers is a box of “Correspondence with or relating to Howard, Roy W., 1917-1933”. (Edward Mandell House Papers. MS 466, Series 1. Correspondence 1858-1938. Box 63, Subtitle: Howard, Roy W. Date: 1917-1933.)

However, there is no correspondence from the years 1917 and 1918 in this collection. It starts with a letter to House from Howard, dated 13 October 1919, welcoming him back to New York on his return from Paris as President Wilson’s Special Representative. House was “confined to his bed” at the time but was hoping to be able to meet Howard “sometime next week”. Whether they met later that month, or sometime before the early summer of 1920, is not certain. But comments in some of the letters suggest that they did not manage to arrange a meeting between August 1920 and the end of 1933. For example, this one from Howard to House on December 23, 1927: “It does seem difficult for us to locate one another among the six million others here in New York”.

On the same day that Roy Howard wrote to House to welcome him home, House explained to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge that he had been taken ill on the day he left Paris and ordered to rest. He did not name his illness (possibly exhaustion brought on by his prolonged efforts since the Armistice to secure agreement for the Versailles Peace Treaties and the proposed League of Nations). But “his condition became worse during the voyage [home], and he left the ship in a state of almost complete collapse”. (He had been very ill with the ‘Spanish flu’ several months earlier, but his October 1919 illness was not considered to be a repeat of this.) (Charles Seymour, The Intimate Papers of Colonel House: The Ending of the War, pp503-504 and p273. (1928).)

14. Emmett King to W.F.L., December 19th, 1918. (Consists of the two-page original letter and an incomplete one-page copy of it.) (Roy Howard Papers) ‘William F. Lynch’ entries in J. A. Morris, Deadline Every Minute, pp79 and 167 refer to his telegraph work in the agency. (Note 9)

15. The US Navy List for 1918 has the following entry: “Archer Emmet King Jr, Lieutenant (junior grade) 5 June 1918; born 14 September 1893. Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps, January 1, 1919, p70.

16. Edward House’s official secretary at the Peace Conference was his son-in-law, Gordon Auchincloss.

17. Emmett King to W.F.L., December 19th, 1918. (Note 14.)

18. See ‘Arthur Hornblow’s Information about the Jackson Armistice Telegram’; and the discussion in ‘’False Armistice cablegrams from France’ on this website.

19. See the False Armistice Cablegram to the American Embassy in London item in ‘False Armistice Cablegrams from France’ on this website.

20. See the Captain R. H. Jackson item in ‘Biographical Details’ on this website.

21. Hugh Baillie to Roy Howard, Washington, July 19, 1919. (Roy Howard Papers) In 1919 “at the age of twenty-eight” Baillie became manager of the UP Washington office – “the youngest man in the bureau . . . then as now the biggest single source of wire-service news”. From: High Tension, the Recollections of Hugh Baillie, p42. (London 1959). There are no recollections about UP’s activities in France during 1914-1918 or his dealings with Roy Howard as UP’s president.

22. See: ‘Some of Brest Staff’: a handwritten note, listed as p25 of the Admiral Henry B. Wilson Papers (most likely M.S. Tisdale’s, in November 1918 Lieutenant-Commander and Assistant to Chief of Staff & Personnel Officer at the Brest Navy HQ). Also: An Account of the Operations of the American Navy in France during the War with Germany, pp8,10. (1919) Available online. And: Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps, January 1, 1919, p518.

23. NH 115448 Telegram Announcing Armistice, 1918. Naval History and Heritage Command Archive (available online). Included incorrectly with two telegrams announcing the Armistice of 11 November, it has thereby been rendered virtually invisible as a historically important document in its own right. It surprisingly turned up during searches in the Archive.

24. L.B. Mickel to Roy Howard, Oklahoma City, August 11, 1919. (There are three copies, each showing different recipients’ initials.) (Roy Howard Papers).

25. In a short item from 22 January 1919, Robert Toomer is described, “before the war opened”, as being “city editor of the Oklahoma City News”. (In Harlow’s Weekly (Oklahoma City), 22 January 1919, page 9, under ‘Two Oklahoma Soldiers Graduate’. Available online through https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc1600526/)

And in a letter in Roy Howard’s Papers, he is named as “M. R. Toomer, Editor” alongside “Raymond Fields, City Editor” of the Oklahoma News. The letter is from G. B. Parker to T. L. Sidlo, May 2, 1923. Apart from taking the copy of the Jackson Telegram for L. B. Mickel, it is not known whether he contributed in any other way to Howard’s False Armistice collection.

26. Naval Signal, 32/34 in the collection at 7 November 1918. (Roy Howard Papers)

27. Naval Signal, 34/34 in the collection at 7 November 1918. (Roy Howard Papers)

28. Naval Signal Negatives, 31/34 and 33/34 in the collection at 7 November 1918. (Roy Howard Papers)

29. I am most grateful to Ken Sutton, curator of the Royal Navy Communications Branch Museum/Library, for information relevant to the signal sheets. The museum/library is located at HMS Collingwood in Fareham, Hampshire.

30. Mrs. John S. Cannon, Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, pp5 & 11. Source: Register of Kentucky State Historical Society , SEPTEMBER, 1919, Vol. 17, No. 51 (SEPTEMBER 1919), Published by: Kentucky Historical Society Stable. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23368552

31. HMS Lion Ship’s Log, “Thursday 7th day of November, 1918”. ADM (Admiralty) 53/46847, 1 October 1917 to 31 December 1918. (The (UK) National Archives) And Battleship Texas BB35 website.

32. Chapter IV, in Webb Miller’s I Found No Peace: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, pp94-95. (London. Special Edition for the Book Club. 1937.)

33. See ‘False Armistice Conspiracy Theories’ on this website.

34. New Britain Daily Herald [Connecticut] Friday, November 7, 1919, p6 under ‘A Year Ago’. (Library of Congress Chronicling America)

35. Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Indiscretions of the Naval Censor. Chapter Ten, ‘Pressmen of Allied Countries’, pp134-137. (1920)

36. For a historical overview of the subject, see Paul Gannon, Inside Room 40: The Codebreakers of World War 1. (2010)

37. See ‘The False Armistice in Britain’ on this website.

38. See ‘The Spa-Senlis Telegrams and the German Armistice Delegation’, on this website.

39. ADM (Admiralty) 137/2064, Grand Fleet Secret & Personal Telegrams, C In C Copies July-Dec. 1918: No 151. C-in-C to Admiralty. 7/11/18. 1034; No 220. Admiralty to C-in-C. 7/11/18. 1419; No 225. Admiralty to C-in-C, 7/11/18. 1657. And ADM 137/927, Home Waters General Operations Telegrams, 7-9 November 1918, page 494. Telegram No. 253 to C-in-C Grand Fleet, 8.11.18. Sent 1853. (The (UK) National Archives)

40. The sources are: A Diary kept by George Lea on board HMS Lion. (The National Maritime Museum, ref. JOD/310); Letters from William Pakenham to MargaretStrickland-Constable. (Written whilst on board HMS Lion). (East Riding of Yorkshire Archives and Local Studies Service, ref. DDST/1/8/1/20); Diaries of Geoffrey Coleridge Harper. (Written whilst on board HMS Indomitable.) (The Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, ref. GBR/0014/HRPR).

41. The Sun, November 9, 1918, p2 under ‘Action on Messages’. (Library of Congress Chronicling America)

42. ‘Explanatory Note’ about what happened to some of the C-in-C’s papers of a confidential nature during re-arrangement by the Grand Fleet secretarial staff in February 1919. Under: National Archives’ Catalogue, Reference The National Archives of the UK. ADM (Admiralty) 137/1895A, Folio 2.