The Broader Story

This article focuses on how the unpublished story of Roy Howard’s time in Brest (the subject of the complementary Part One article) was enlarged by the publication of accounts by other eyewitnesses of events in Brest at the time, and changed by Howard himself for his published memoir. An analysis and commentary on some aspects of the narratives in both Parts One and Two is contained in an Addendum.

The principal other eyewitnesses were Arthur Hornblow Jr, C. Fred Cook, Admiral H. B. Wilson, and John Sellards. Admiral Wilson and John Sellards never publicised their parts in the False Armistice events in Brest; but Wilson did leave a ‘False Armistice Folder’ of private papers which has been used here. (His side of the story is elsewhere on this website.)

Arthur Hornblow’s original account was called Fake Armistice, but it was never published as such. He changed parts of it and the title during 1921 and had the resulting Amazing Armistice published in November 1921. C. Fred Cook had two consecutive False Armistice anniversary newspaper features published in November 1924 and 1925. And following Hornblow and Cook, Roy Howard’s own memoir, the ‘Premature Armistice’ chapter of Webb Miller’s I Found No Peace: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent appeared in 1936. Information from these sources is brought together here for the first time, revealing similarities, differences, contradictions and, in Howard’s memoir, some factual distortions.

Brest in November 1918 – some context

On the tip of the Brittany peninsula, some 387 miles (623 kilometres) from Paris by train, Brest was the principal entry port for US troops shipping to France after April 1917. The Americans had two major military facilities there: an army base under the command of General George Harries; and the main base and headquarters of US naval forces in French waters under the command of Rear Admiral Henry B. Wilson. There were of course French Army and Navy forces stationed there but no British forces at the time, although there was a British Army line-of-communication base there supporting front-line units.

The town had a telegraph transmitter and receiver, situated in its Post and Telegraph (P&T) building, for sending/receiving cablegrams across the Atlantic Ocean. The French Telegraph Cable Company (Compagnie Française du Télégraphe de Paris à New York) owned the undersea cable between Brest and New York City.

The local newspaper, La Dépêche de Brest, leased an overland telegraph wire to Paris (possibly also owned by the French Telegraph Cable Company) which provided it with a private line to the capital. Importantly, Roy Howard’s United Press (UP) Paris office had an agreement with La Dépêche allowing it to use the line for news it sent from Paris to Brest for onward transmission to New York City by the undersea Atlantic cable. Alone among the American news agencies, this enabled UP to bypass the usually crowded public telegraph service from Paris to Brest, thereby enjoying a quick communication between its Paris office (Rue Rossini, Montmartre) and New York City office (third floor of the Pulitzer Building).

The time in Brest, as in the rest of France and Britain (Allied Time), was five hours ahead of New York City Eastern Standard Time.

Development of the broader story

One of the first things Howard did on returning to the United States was to speak to Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels in Washington, DC, on 19 November, ostensibly “to express his appreciation” for Admiral Wilson’s statement exonerating him and United Press from blame for the 7 November false armistice news. III.1 A day later, Howard spoke at length to journalists about what had happened in Brest, which newspapers reported on 21 November. Two days after this, the Editor & Publisher featured an exclusive interview Howard had given them on the same matter.

Howard’s pronouncements about the False Armistice after returning to the United States.

The following is extracted from the New York Times’ report of Howard’s 20 November press statement:

“It was about 10 o’clock in the morning (French time) when I first learned of a rumor that the armistice had been signed. The report was current in both French and American Army circles in Brest when I arrived that morning to embark for the United States. I put in the entire day endeavoring to confirm the report. But it was not until about 4 o’clock in the afternoon that Admiral Wilson was notified . . . on what I know he had every reason to believe was official authority that the armistice had been signed.

The announcement had been made by the local Brest newspaper and the civilians, soldiers, and sailors had their celebration under full headway before I was able to get from Admiral Wilson personally a copy of his written announcement and his personal assurance that the bulletin was official.

The Admiral then sent his personal aid with me to assist me in filing the dispatch, as I do not speak French fluently.

It was a fact that all Brest, including operators and censors, accepted the news as official, and was celebrating at the time that caused my wire to pass the French censorship at Brest unchallenged.”

The New York Times decided that the statement was tantamount to an excuse for Howard’s false armistice cablegram. III.2

In his 23 November Editor & Publisher exclusive, under the subheading “Birth of the Armistice Rumor”, Howard related that he “arrived in Brest . . . expecting to start for home on a transport, called upon Gen. Harries, in command of the military base, shortly after 10 A.M., and . . . at Army Headquarters . . . first heard that an armistice had been signed. This was only a rumor, however, which could not be confirmed, though [he] found that the French military and the local newspaper, La Depeche, also had heard the report. It was later in the day – about four o’clock – when [with] Major Fred C. Cook . . . [he] called upon Admiral H.B. Wilson [and was told the rumor was confirmed].”

Howard continued his interview with a repetition of most of the dialogue in Admiral Wilson’s office he had composed for his 9 November letter to Phil Simms in Paris. III.3 He expanded the above sentence in his press statement about leaving with the Admiral’s armistice news after being told he could “use” it to: “I suggested to the admiral that I would probably encounter some linguistic difficulties, and asked if Ensign Sellards might accompany me to get my cable off. To this he readily assented, and after I had typed a verbatim copy of the admiral’s dispatch the message was filed at the cable office by messenger from La Depeche.” III.9a

The rest of the account restates what he said to Phil Simms about hearing that French authorities were denying the armistice news was official, looking for Admiral Wilson and learning that he too had been told it was not official, and how he “Did Not Shirk Responsibility” but readily agreed to sign a “complete statement to our clients of what had happened”.

He ended by acknowledging that his armistice cablegram “had cleared the French censor even though not official”; and claiming that he “sought the reason for this from the head of the French Bureau at Brest, Capt. Gambey”, who told him “the news of the armistice had reached the cable and censorship office sufficiently ahead of [his] bulletin to allow the celebration to get under way there”. As a consequence, “in the excitement [his] urgent message was shot through to New York, and more than two hours later the operator bethought himself and sent the message to the censor!!!” – an elaboration on his press statement, reported on 21 November, relating to why his cablegram went through. III.4

What is new here is Howard’s claim that when he arrived in Brest there was a rumour circulating that the Germans had actually signed an armistice, and all the military officials he met during the morning and early afternoon had heard it. (More about this below.)

What Howard wanted immediately after his return from France was to find out what he called “the whole story” about the False Armistice, information that would reveal what really happened on 7 November and which he believed Allied authorities were withholding from the public. He had success in finding a few items of general information about it, but not, it seems, what he was hoping for. III.5 And his interest in the matter had probably subsided until he heard from Arthur Hornblow during the summer of 1921.

Hornblow was the American Army G-2 (SOS) Chief Intelligence Officer at the US Army Base in Brest in November 1918 and had met Howard there. In June 1921, he sent him a copy of Fake Armistice, and as Howard was one of the named protagonists, requested his comments on it and, by implication, approval for its publication. Howard consented in a long letter setting out his reactions to the text.

Hornblow’s article tactfully refuted Howard’s November 1918 press statement and Editor & Publisher explanations that the armistice cablegram passed without being cleared by the local censors in Brest because (essentially) they were outside celebrating the peace news when the cablegram was taken to their office in the Post and Telegraph (P&T) building. Fred Cook’s November 1925 False Armistice anniversary feature also queried Howard’s simple, but plausible explanation. Partly because of such doubts regarding the armistice cablegram’s transmission, Howard changed his 1936 explanation by attributing key roles to Admiral Wilson and his aide John Sellards in the process.

(For convenience, in the rest of this article the 7th November in Brest is divided into the following parts of the day: 9:00 am to about 4:00 pm, 4:00 pm to about 4:20 pm, 4:20 pm to about 6:30 pm, and 6:30 pm to midnight. What Hornblow, Cook, and Howard wrote about the 7th is therefore arranged within those four parts.)

Thursday 7 November

9:00 am to about 4:00 pm

Information from Arthur Hornblow’s Fake Armistice

Hornblow wrote Fake Armistice in New York City after the war – exactly when is not certain – but in June 1921 he posted copies to Roy Howard and Admiral Wilson and, as a result of their criticisms, amended it and changed its title to Amazing Armistice. Fake Armistice, therefore, was never published as such, but Amazing Armistice was – in the November 1921 issue of Century Magazine. I. Arthur Hornblow Jr; and II. (Extracts from both versions are in this colour.)

One of Lieutenant Hornblow’s duties in Brest was to look after American newsmen arriving there. He had not met Howard previously but had favourable reports about him which graded [him] among the highest for the degree of attention to which they were entitled wherever they went . . . some one who very nearly approached the exalted ranking of “distinguished visitor”.

I sensed something of what goes to make the great newspaper man!

Not long after 9:00 am, one of Hornblow’s team on duty at the railway station informed him of Howard’s arrival, and he expected Howard to introduce himself at his office a short time later – most newspapermen made it a point of reporting promptly at the office of the I.O. in order to hear if any news had broken locally, and to be facilitated generally in getting around and seeing things and people. But it was not until shortly before noon (around three hours later) that Howard strolled in casually and asked Hornblow to arrange a passage for him on a faster ship than the one already booked for him in Paris which took two weeks to reach the United States and was due to leave at two o’clock that afternoon. He was anxious to organise a United Press team and travel back to France with President Wilson’s peace conference entourage – the man knew even then that Wilson was coming!

Hornblow was able to do so – a transfer to S.S. Leviathan sailing on the 8th and able to complete the voyage in six days or so – and in response to another request took Howard to US Navy Headquarters on President Wilson Square to meet Admiral Henry B. Wilson. They left Hornblow’s office about noon. On the way they stopped outside the La Dépêche de Brest building, the town’s local newspaper, also on President Wilson Square. Here they read about a German armistice delegation heading for the Western Front. As we turned . . . into the old square – Place du Président Wilson – we paused before the office of Brest’s daily newspaper La Dépêche to examine the bulletin and saw that the Germans had evinced a desire to quit and that their plenipotentiaries were reported to be coming across the lines to sue for an armistice. A small, excited crowd was discussing the tidings and waiting eagerly around for more.

The sight of the Dépêche office inspired Howard to pay it a visit, due to his company’s having relations with it that I was soon to learn. Inside the building, they stopped first in the telegraph room, which was nearest the door, and Howard entered animatedly into conversation with the operator on duty in a French that was as utilitarian as it was full of gestures!

Hornblow gradually gathered a fact that was to have tremendous bearing later on. It seems that there were but two ways of communicating by telegraph between Paris and Brest. One was by the regular wires of the public telegraph service, the other was by the private wire of La Dépêche. Users of the public service – and this included correspondents sending their communications through to be cabled to the States from Brest – had to wait their turn – a matter usually of several hours, and the United Press scored a brilliant mechanical beat by getting the permission of La Dépêche to share its special wire, thereby avoiding delays in transmission to Brest and being able to hop onto the cables ahead of its competitors. UP messages would first pass through the necessary censorship [in Paris], then . . . be put on the private “Depeche” wire and in this way be sped to Brest.

Hornblow and Howard then went on to Admiral Wilson’s Headquarters. As the Admiral was elsewhere, his aide Ensign John Sellards booked Howard in to meet him at 4:00 pm and Hornblow showed Howard a few of Brest’s sights (nothing much to see), took him to lunch at the Navy Club (no location), accepted his invitation to take some fellow officers to dine with him later that evening, and – after two o’clock – left him at the Continental Hotel, where Howard had managed to find accommodation. [Fake Armistice, June 1921, pp.3-7] III.6

Howard read Fake Armistice three times before replying to Hornblow’s request for suggestions as to changes in the statements of fact, and sent him a typed, compact letter filling six sides of paper. He complimented Hornblow on not merely attempting to sell an article to some magazine but [also on trying] to give a truthful close up picture of an event which we must admit was of more than passing interest to several million people. Observing that having played the principle (sic), or possibly I may say the more tragic role in this particular drama [Howard wanted] to get across to [Hornblow his] point of view on one or two seemingly inconsequential statements which . . . in my opinion not only have a direct bearing on the impression your article will create of my status as a journalist, but also to some degree have a bearing on the accuracy of your article. And hoped that Hornblow would not regard any statement . . . calculated to refresh [his] memory or alter any of [his] personal opinions or deductions” as being “hypercritical” or be “averse to giving consideration to them.

Towards the end of the letter, Howard urged Hornblow to include in [the] article . . . the fact that immediately upon [his] arrival in Brest [Howard] reported directly to General Harries’ headquarters and their (sic) heard repeated a report which [he] had first gotten at the station at Brest to the effect that the armistice had been signed. At General Harries’ headquarters everyone expressed the belief that the report, as yet merely an unofficial rumor, was true, and all expected that the confirmation would be coming along at any moment.

Howard was alluding here to what Hornblow had said about their activities between Howard’s arrival in Brest and return to the Continental Hotel after their lunch at the Navy Club. Hornblow had not remarked that there were rumours already circulating in Brest about a German armistice having been signed. Howard insisted that there were, and that Hornblow had failed to make any mention of the fact that we found the same rumor at the French army headquarters and among the subordinates at Admiral Wilson’s headquarters. And informed him that as a matter of fact following my leaving you after luncheon I returned to Harries’ headquarters and found everyone so excited there over the rumour that the General sent Major Cook out with me in an effort to see if we could round up any confirmation of the rumor.

He finished the paragraph with the following noteworthy explanation:

I cite this fact as being of importance only because of the persistent effort made by the New York Globe, the Associated Press, and one or two other newspapers particularly unfriendly to the United Press, to create the impression that I had filed a wild rumor that did not have any semblance of official justification. [Roy W. Howard to Arthur Hornblow, San Diego June nineteenth 1921, pp.1-2 and 5-6. Hornblow Papers.]

In deference to Howard, Hornblow inserted a few words about peace rumours being current in Brest before Admiral Wilson received his armistice news from Paris. He added to the part about their reading the La Dépêche bulletin on the German armistice delegation that oddly enough, a rumor was seeping through [the crowd] to the effect that an armistice had already been signed, and Howard told me that he had heard the same thing when he came in at the station that morning. And, in a later part describing his reaction on being told Admiral Wilson’s Headquarters had announced that an armistice had been signed, that he was astounded at the suddenness with which truth had been given to the odd rumor that had hovered over Brest all day – two of a number of changes Hornblow made following Howard’s comments on Fake Armistice before its publication under a new title. [Amazing Armistice, November 1921, pp.92-93] I. Arthur Hornblow Jr

Information from Fred Cook’s November 1925 False Armistice newspaper anniversary feature

In November 1918, Major Fred Cook was stationed at the American Army Base in Brest, and met Roy Howard there during the afternoon on 7 November. When he left the army, Cook resumed his pre-war job with the Evening Star newspaper in Washington, DC. He read Hornblow’s Amazing Armistice, and a few years later decided to publish his own first-hand account of the False Armistice in Brest. (Excerpts in this colour.)

His newspaper printed two False Armistice anniversary stories based on his recollections: a short one for the 11 November 1924 issue, in which he avoided identifying Roy Howard by name; and a much longer one on 11 November 1925 for the seventh anniversary. Both were concerned primarily with events after Cook met Howard, the 1925 one with a particular focus on the facts so far as the actual giving out of the [armistice] “news” is concerned. III.7

Whether Roy Howard read Cook’s 1924 item is not known; but he read his 1925 article on the way from San Francisco to Chicago, after a three-month business trip to East and South East Asia, and decided – not with any desire to be meticulously critical – to write to Cook about it. He assured Cook that his account of the developments of that somewhat hectic afternoon [corresponded] very closely with [Howard’s] own remembrance. But he wanted to check up . . . on one point on which [Cook’s] remembrance [was] at variance with [his] own.

The point in question was the absence from Cook’s article of any reference to the presence of rumours in Brest that Germany had signed an armistice. Howard felt that Cook had given the impression that Admiral Wilson’s report of the signing of the armistice was the first news we had on the subject. However, you will recall, Howard insisted (as he had to Hornblow in June 1921 on the same matter) that the rumor . . . the armistice had been signed was current all over Brest on 7 November before Howard arrived there. He maintained that an M.P. who met him at the railway station was the first to speak to him about it, that Lieutenant Hornblower (sic) at G-2 had [it] when [he] checked in with him; General Harries had heard it when [he] called on him with [Hornblow] and thought it was quite possible that the report was true; and that at French Headquarters they had the same vague rumor. He noted that he had filed nothing on this rumor, but reminded Cook that when they were both at Navy Headquarters and Admiral Wilson told them his news was from Paris, they were surprised not because the armistice had been signed, but . . . rather [because] the Admiral had succeeded in getting an official announcement to that effect ahead of everyone else. [Roy Howard to Fred Cook, 28 November 1925, p1.]

Fred Cook’s article had already been published when Howard wrote to him “c/o The Star” in Washington, DC. So, assuming Cook received the letter and would have been willing to do so, it was too late for him to change his article to accommodate these and several other points Howard raised that were “at variance” with Cook’s recollection of them (below).

Information from Roy Howard’s 1936 memoir

Howard’s own account of 7 November 1818 from his arrival in Brest to when he met Admiral Wilson just before 4:00 pm contains the details he criticised Hornblow and Cook for leaving out of their articles. (Excerpts are in this colour.)

Howard’s first and most consequential day in Brest started for him at around 9 o’clock in the morning French time (4:00 am in New York) when his train pulled into the Gare de l’Ouest after an overnight twelve-hour journey from Paris. He had gone to Brest apparently to take a ship back to the United States. He had been given instructions to report to General Harries at the US Army Base, and a member of Lieutenant Arthur Hornblow’s G-2 (SOS) Army Intelligence team met him to take him to Hornblow’s office there. On the way the soldier, quite casually, told him, that the Armistice had been signed; it was not official – the news had travelled via the grapevine and was general throughout the base.

They hurried to Lieutenant Hornblow’s office; Hornblow too had heard the armistice rumour, but had no official confirmation yet. He arranged for Howard to travel to America on board the S.S. Great Northern (no departure time given), conveyed an invitation to lunch with General Harries at midday and escorted him to the Continental Hotel, where he would be staying. From here they went to US Navy Headquarters to give Admiral Wilson a letter of introduction Howard was carrying from Josephus Daniels, the US Secretary of the Navy, and to try to find out more about the peace news – Hornblow’s own interest in the armistice rumour [was] as keen as [his] own.

The sailor on desk duty also knew about the rumour but was unaware of anything official for the Admiral about an armistice; Wilson was not there at that moment and not expected to be back until 4:00 pm. So, Hornblow took Howard to meet the local French Commandant who suspected that [the rumour] was true but also had no confirmation. Afterwards he left him with General Harries at Army Headquarters for his luncheon meeting – for which Hornblow could not remain. Staff here were in high spirits as a result of the rumour but had so far failed to verify it. After lunch with the General, and accompanied by Major Cook, Howard continued his quest for [armistice] information before heading to Navy Headquarters for his 4:00 pm appointment with Admiral Wilson. Throughout the town there was a tense air of cheerful expectancy among civilians and military alike. The American navy band was playing to a crowd of civilians and servicemen from a bandstand in the square, and the Admiral was now in his office. The time was 4:10 pm. [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.77-81]

Thursday 7 November

4:00 pm to about 4:20 pm

Admiral Wilson’s armistice news, and Howard’s armistice cablegram

The false armistice news from Paris had arrived at Admiral Wilson’s headquarters shortly before 4:00 pm. Between 4:00 and 4:20 pm, Howard’s cablegram containing the news was put together and transmitted to New York City, arriving around midday EST – ahead of the early afternoon newspapers in that time zone, and of late morning ones farther west.

The sequence of events during those twenty minutes took place in three separate buildings: 1) the American Navy Headquarters; 2) the La Dépêche building; and 3) the Post and Telegraph building. From different sides, each building overlooked President Wilson Square and its ornate central bandstand. III.6

1) At American Navy Headquarters, in Admiral Wilson’s Office

From Hornblow’s Fake Armistice and Amazing Armistice

As Hornblow was not with Howard between 4:00 and 4:20 pm, his Fake Armistice account of what occurred in Admiral Wilson’s office, the La Dépêche and the Post and Telegraph buildings was presumably based on his own subsequent enquiries and information Howard gave him.

In Fake Armistice, he recounted that promptly at four o’clock Howard had been presented to Admiral Wilson. They had not been chatting more than a few minutes when an orderly entered with a telegram for his chief. Reading it, the Admiral gave vent to an explosive explanation and bounding enthusiastically from his chair handed the message to Howard. The latter beheld an official communication signed by Commander Jackson, the naval attache at our Paris embassy . . . . Wilson at once despatched orderlies to bulletin the great tidings in the public square and ordered the band out to help the populace celebrate [and] flags were spread all over the tall navy building . . . . Admiral Wilson was entirely willing that Howard should take advantage of [the armistice news], not because he was especially desirous that Howard should register a “beat” but because he was anxious for the people back home to have the news as soon as they possibly could . . . . In company, therefore, with Ensign Sellards to assist him in getting his message past the local French censor, Howard dashed to the Postes. [Fake Armistice, June 1921, pp.8,9,10]

As well as to Roy Howard, Hornblow had sent a copy of Fake Armistice to Admiral Wilson for his comments, and points the Admiral made about this passage led Hornblow to change most of its details. So, in Amazing Armistice, Howard having arrived promptly at four o’clock, and after chatting for a while, the Admiral remarked that he had just received a message which might possibly interest Howard and handed it to him for his perusal. Howard beheld an official telegram, signed by Commander Jackson of Admiral Wilson’s office in Paris and naval attache at our Paris embassy announcing an 11:00 am armistice and 2:00 pm cessation of hostilities. The Admiral allowed Howard to use the message; and with Ensign Sellards to assist him in arranging things Howard hurried out of Navy Headquarters heading for the Postes. [Amazing Armistice, November 1921, pp.93-94]

Importantly, in deference to the Admiral, Hornblow had removed the unambiguous allegation in Fake Armistice that Ensign Sellards went with Howard “to assist him in getting his message past the local French censor” (for which Howard was most probably Hornblow’s source); and replaced it with the ambiguous Sellards went with Howard “to assist him in arranging things”. But at the same time in Fake Armistice, seemingly anticipating inferences readers might take from the allegation, he had pointedly dismissed the possibility that, acting on Admiral Wilson’s instructions, Sellards made sure the censors allowed the peace news to go to New York City. He did so by declaring that not even the Admiral in person could have caused the local censors to let by so portentous a message without having the O.K. of either the Ministry of War or the Paris censorship office (p11). And he changed it only slightly for Amazing Armistice to read no one in Brest, of whatever exalted rank (p95) could have done so . The only reason the cablegram left Brest, Hornblow emphasised in both versions, was that it appeared to have come from Paris already censored.

Howard did not object to these statements disclaiming that Wilson and Sellards made sure the armistice cablegram was transmitted; he ignored them, and later embodied the unambiguous allegation against Wilson and Sellards in his memoir. (The allegation itself can be traced to 8 November 1918 official reports to the US State Department about the false armistice news. With other official wartime documents, they were only made public in 1933. III.8)

In both Fake Armistice and Amazing Armistice, it is interesting that Howard is not accompanied by Major Cook while in Admiral Wilson’s office; and that he saw the armistice news was from Captain Jackson, the US Naval Attaché in Paris. Admiral Wilson told Hornblow in July 1921 that when he showed Howard the news he did not disclose the sender’s name. If this was so, Howard guessed correctly on 7 November who the sender was: that evening, he suggested to Phil Simms in Paris that he talk to Jackson about it. When Hornblow himself became aware the news carried Jackson’s name is not certain, but, carried over from Fake Armistice, Amazing Armistice made it public.

Howard did not comment on either point, noting only that Hornblow’s “quotations of the armistice message” were not “literally correct”: he omitted that American forces had taken Sedan; and Howard offered, for the sake of accuracy, to provide him with “an exact duplicate” of it. Hornblow evidently failed to correct the omission for Amazing Armistice.

From Fred Cook’s 1925 newspaper False Armistice anniversary feature

On 15 November 1918, Cook had written an attestation, at Howard’s request, outlining what had occurred when he and Howard were at Navy Headquarters on 7 November 1918. The statement has just a few bare details about the short time they were in Admiral Wilson’s office, and Cook incorporated them in his more substantial November 1925 recollections (presented in this colour):

A few days prior to November 11, 1918 – to be exact, Thursday, November 7 – the civilized world literally went mad because of an announcement, which proved to be erroneous, that the war officially had ceased . . . The story of “the amazing armistice” has been written and published, but I have not read any account that coincided with the facts, so far as the actual giving out of the “news” is concerned.

It so happened that I was present, a listener and close observer, when the historic episode occurred.

Only three other individuals are aware of their own knowledge of just what took place. I will here set down the exact truth, as to words and actions, to the best of my recollection. (The other three individuals alluded to were Admiral Wilson, Roy Howard, and James Sellards.)

Cook explained that he was introduced to Howard during the early afternoon at General Harries’ Army Base, was told that Howard was sailing for home [and was] anxious to meet Admiral Wilson before he [left]. General Harries asked him to arrange to present [Howard] to the admiral and Cook took him to Navy Headquarters, a tall building overlooking President Wilson Square and about five city blocks from the Army Base. The Admiral’s office was on the fifth deck, through a room occupied by Ensign Sellards, Wilson’s personal aid, confidential secretary and interpreter.

Cook introduced Howard, and Sellards left the room to speak to the Admiral in his office. A short time later, Wilson came out of his office holding a piece of paper in his hand. Before Cook could utter a word, the Admiral told them it was a telegram from Jackson, in Paris, saying the armistice was signed at 11 o’clock this morning, effective at 2 o’clock this afternoon. [They] all were aware that ‘Jackson’ was Comdr. Jackson, the naval attache at the United States Embassy in Paris. There was absolute silence for a second or two until Howard asked whether he might use the information. After some hesitation, as though in doubt how to reply, Wilson said slowly and hesitatingly “Why, I suppose so”, whereupon Howard uttered a hasty “I’ll see you later” and rushed out of the building.

From the open window, Cook watched Howard run across the square to the French Post Office, which was also the telegraph and cable office, located on a corner diagonally opposite, and saw crowds gathering to read the Admiral’s news which was now on display outside La Dépêche. Instructions were issued for the news to be announced to people listening to the American navy band in the square and for a huge flag to be hung across the Headquarters building. As pandemonium started spreading, Cook left the building and made his way back to the Army Base to give General Harries the news. The General believed it but, because he had not yet been informed by American Army authorities, the base attended to business and continued quietly at work. [The Evening Star, Wednesday, November 11, 1925, p.4, under ‘Real “False Armistice” Story Is Now Told By Eyewitness’. III.7]

Cook had restated (from his 15 November 1918 statement) that Howard asked permission to use the news from Paris, and went alone towards the P&T building. But now added that the Admiral disclosed to him and Howard that the news came by military wire from Commander Jackson, the naval attaché at the Paris Embassy. And like Arthur Hornblow, he left out the Sedan detail when quoting the armistice news.

In his 28 November 1925 letter to Cook about the article, Howard complained that the story indicated that only seconds elapsed before Howard rushed off with the news and ran to the French Post Office. Let your mind run back again, Howard suggested, [and] you will recall that we stood and talked to Admiral Wilson for at least several minutes [while] I interrogated him [to make sure it] was actually an official announcement [and] delayed long enough to secure a copy of the dispatch Admiral Wilson held in his hand.

The sentence about seeing him run across the square to the cable office after he dashed out of Wilson’s office on his own was an instance of Cook’s memory having failed him, Howard claimed, noting that having agreed he could use the armistice news, the Admiral then wondered whether he spoke French with any fluency – he did not – [and] ordered Ensign Sellards to go with [him] to the cable office (P&T) and help expedite the dispatch through the Censor. However, as a matter of fact he and Sellards did not go straight there: instead, they went directly to the office of La Depeche where the dispatch was typed on one of the cable blanks used in that office for transmitting the United Press dispatches which came from Paris to the cable head over a private wire maintained by La Depeche and the United Press jointly. Subsequently [they] went to the cable office on the opposite side of the square from the newspaper office. [Roy Howard to Fred Cook, 28 November 1925, pp.1-2.]

Howard had not drawn attention to any supposedly faulty observations or important omissions in Cook’s attestation of 15 November 1918. But now, as well as ignoring armistice rumours in Brest that day, Howard accused Cook of overlooking the “fact” that Sellards went with him “to the cable office” having been ordered by Admiral Wilson to “help expedite the dispatch through the Censor”. Arthur Hornblow had included this point in Fake Armistice but withdrew it for Amazing Armistice after Admiral Wilson objected to it. (‘Unambiguous allegation’ above)

His assertions here about Admiral Wilson and Sellards may well have been prompted by these two sentences in particular from Cook: In my judgment the most remarkable incident of the ‘false armistice’ was the fact that the message filed by Mr. Howard was dispatched immediately, and without question. There was no demand, so far as I am aware, that it be censored and approved. (Hornblow had made similar points about the cablegram in Amazing Armistice.) Howard was sensitive and defensive about implied queries like this relating to his armistice cablegram’s leaving Brest on 7 November unhindered, and his claim that it was a “fact” Admiral Wilson ordered Sellards to go with him to “expedite the dispatch through the Censor” became his primary repudiation of them.

I am taking the trouble to bring these points to your attention, Howard assured Cook towards the end of his letter, not with any intention of appearing critical of your article, but rather because I believe that on second thought you will recall conditions to have been as I have stated them. [Roy Howard to Fred Cook, 28 November 1925, p.3.]

Eleven years later, in Premature Armistice, Howard stated what those ‘conditions’ in Admiral Wilson’s office were:

The Armistice has been signed . . . . It’s the official announcement.

Ensign James Sellards, personal aide, secretary, and interpreter, took Howard and Cook through to Admiral Wilson’s office where the Admiral was standing by his desk holding in his hand a sheaf of carbon copies of a message. An orderly left to give some of them to La Dépêche and to the American Navy Band playing in President Wilson Square. Another orderly went to tell the duty officer to hang out the biggest flag they had across the headquarters building.

To Major Cook’s enquiry, the Admiral responded that the Armistice had been signed, handed Cook a copy of the message, and assured them it was official – just received . . . over my direct wire from the Embassy – from Jackson. Cook commented that he and Howard had been chasing this rumour all day. And Howard asked the Admiral whether he had any objection to [his] filing it to the United Press. “Hell, no, . . . this is official. It is direct from G.H.Q. via the Embassy. It’s signed by Captain Jackson, our Naval Attaché at Paris. Here’s a copy of what I have just sent to Dépêche. Go to it”, replied Wilson. The Admiral then instructed Ensign Sellards to go with Howard to make sure his cable cleared through the censorship, [to] stay . . . until he gets [it] through, [and to] bring him back here. [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.80-82]

Thus, in 1936 Howard stated, just as Cook had in 1925, that Admiral Wilson told them his armistice news was from Captain Jackson in Paris. And (again just as Cook had written in 1925) Sellards was already in Admiral Wilson’s office; he was not coming “rather out of breath” from the La Dépêche building having failed to leave the armistice news with the editor only to be sent back with it, as he was in Howard’s letter to Simms in November 1918. III.3 Instead, Howard now states that Wilson chose an orderly to take the news to La Dépêche (and to the US Navy band master in the square).

Howard himself, Hornblow, and Cook had all noted previously that Howard asked Wilson for permission to “use” the armistice news. But here, Howard enlarged this to permission specifically to “file” it “to the United Press”, that is, for permission – which Wilson allegedly granted – to send it for publication in the American newspapers. And then asserted that the Admiral instructed Sellards to go with him to make sure the censors passed his armistice cablegram. But he is the only participant in the 4:00 to 4:20 pm events in Brest to do so. Cook did not support the claim. Hornblow removed it for Amazing Armistice. And both Admiral Wilson and John Sellards flatly denied it.

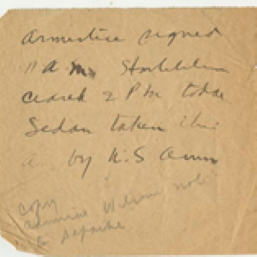

Remarkably, in Howard’s archive is a transcript in ink of the Jackson message, which is assumed here to be the one Admiral Wilson handed to him or to Sellards. It reads (unclearly in parts): “Armistice signed 11 AM Hostilities ceased 2 PM today Sedan taken this AM by US Army”. Under it, in pencil and also not clear in parts, is an annotation that it is a copy of the note Admiral Wilson sent to the La Dépêche newspaper.

[I. Howard Papers, TMG1: 1/34.]

2. In the La Dépêche building

For what occurred after Howard left Navy Headquarters, the only available first-hand evidence is Howard’s, and is in his 9 November 1918 letter to Phil Simms and his Premature Armistice chapter in Webb Miller’s book. (His November 1918 press statement and Editor & Publisher article do not cover his crucial few minutes in La Dépêche.)

From Arthur Hornblow’s Amazing Armistice

(As Hornblow was not with Howard in the La Dépêche building, detailed information for his account may have been obtained from the La Dépêche staff and its editor, Louis Coudurier, whom he later met officially on behalf of General Harries, the American Army Base commander.)

Having already explained how the privileged use of La Dépêche’s telegraph link to Paris worked to UP’s benefit (above), Hornblow continued by describing how the newspaper’s own telegraph equipment was used to put together Howard’s armistice cablegram. His account here from Amazing Armistice is essentially unchanged from that in Fake Armistice:

Probably . . . Roy W. Howard was the only man in the world who could have sent the message as it was sent or who could have sent it at all.

Howard and Sellards left Navy Headquarters with the armistice news and headed for the P&T. However, desiring to file a typewritten message so there would be no possible misunderstanding or misreading by the French cable operator Howard dived en route into the nearby telegraph room of “La Depeche” and demanded a type-writer, explaining hurriedly his reason.

The telegraph editor took over. Using the newspaper’s telegraph instrument, he first typed the words on paper tape with his local telegraph key – it was possible to type on the ribbon with the local telegraph key as well as with the transmitting-key in Paris. Then tearing off the tape, the obliging Frenchman pasted it as usual on a telegraphic form and, lo! the message was clear and ready for immediate filing.

It is highly important to note that the [telegraph] instrument in “La Depeche” office was of the ticker-tape variety commonly used throughout France, being a machine which typewrites its own messages on paper ribbon. When the United Press communications were ticked off in “La Depeche” office by the sending operator in Paris, the tape recording the message was cut up, pasted on the usual telegraph form, sent by messenger across the place to the post-and-telegraph office, and filed for the cables. Long practice had accustomed the Brest cable censors to recognize these United Press messages, and, in view of their having already been censored in Paris, to accord them prompt transmission without further censoring. The end result, crucially, was that Howard’s message was now identical to a UP telegram from Paris: it looked exactly as though it had been transmitted from Paris as were all other United Press messages and had been censored there! (Hornblow’s italics.) Moreover, in his generosity Howard had put Simms as the sender, wanting to share the glory of his ‘beat’ with Phil Simms – the man who signed all the messages that came from Paris and whose name was the stamp of proper procedure. Consequently, the cablegram was not blocked but was speedily forwarded to New York City, where the American censors let it through believing it had already been seen in Paris and Brest.

Hornblow was certain that Howard had not deliberately made sure the telegram looked like one from his office in Paris and already approved by the Paris censors, and therefore that he had not cheated to be first to the American papers with the peace news. It was [an] unintended strategy of Howard’s that enabled him to get his cable past the local censors . . . ‘unintended’ because it is inconceivable that any man, however alert, could, under the circumstances, have thought up so extraordinarily clever a devise. [Amazing Armistice pp.92 and 95]; could have thought up so infernally clever a scheme. [Fake Armistice, June 1921, p.11] III.10a

Howard’s only comment on the above, in his lengthy June 1921 letter criticising Fake Armistice, was a short, cryptic one about Hornblow’s description of the false armistice cablegram. Regarding the printer tape element in the story, he told Hornblow that his outline [was] off in a slight way that would considerably alter [the story]. However, because no harm and no injustice is done to anyone by your record of this detail as you remember it, he would not be a spoil sport by going into this matter. What you don’t know on this point, he remarked enigmatically, won’t hurt anyone and you can have a clear conscience. [Roy Howard to Arthur Hornblow, San Diego, June nineteenth, 1921, p.4. Hornblow Papers.] Why Howard made this comment is open to conjecture. (See ADDENDUM)

Four years later, in November 1925, Fred Cook wrote that Howard rushed alone straight from Navy Headquarters to the French Post Office to have Admiral Wilson’s armistice message cabled to the United States (above), so Cook had nothing to contribute to Hornblow’s information about what occurred in the La Dépêche office. Eleven years later, Howard described briefly how his cablegram was prepared for him, and explained its wording.

From Premature Armistice

It was my intention to retype the message . . . on the regular form of cable blank.

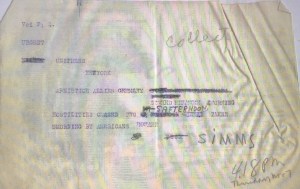

On the way to the Cable Office, he and Sellards stopped at La Dépêche, which was a client of the United Press. Howard was going to use one of the newspaper’s typewriters to type the armistice news on a regular form of cable blank, address it to UP in New York City, and make a carbon copy for his records. But there were no typewriters with a standard keyboard. The telegraph operator handling the U.P. wire – the La Dépêche telegraph link to Paris – took over and typed it for him, not directly onto a blank cable form, but first onto the regular tape used for Press telegrams. This was then pasted onto a regular cable blank, and read:

UNIPRESS NEWYORK

URGENT ARMISTICE ALLIES GERMANY SIGNED ELEVEN SMORNING HOSTILITIES CEASED TWO SAFTERNOON SEDAN TAKEN SMORNING BY AMERICANS

HOWARD SIMMS

Howard pointed out that:

UNIPRESS was the cable address of United Press.

SIMMS was the surname of William Philip Simms, the UP Paris manager.

He included Simms’ official Press Card number (not shown) because it was needed for collect messages filed to United Press. III.9b

The only difference between his and Admiral Wilson’s message was the deletion of the word this and its replacement by an s at the beginning of morning and afternoon. (Examples of ‘cablese’ words which reduced the total word cost.) [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.82-83]

The Armistice Cablegram’s First Draft?

The sheet below is one of La Dépêche‘s distinctive sheets used for telegrams coming from Paris over its leased wire – its “fil télégraphique spécial et direct de Paris à Brest” (printed below the newspaper’s name). On it is an image of the newspaper’s building and a header with the newspaper’s name, postal and telegraphic addresses, and the name of its editor, Louis Coudurier.

The creased sheet has been folded and copied in two halves. This is the top half.

The bottom half carries the typed armistice message, illegible in parts because of pencil-deletions; and above it “Voi P;Q.” indicating for transmission from the Cable Office. Added in pencil are “Simms” (presumably positioned after his crossed-out four-digit press card number), “Collect”, and “4.18 PM Thursday Nov 7”.

[TMG1: 29/34 & 30/34]

It looks like the original typed version, with amendments, of the handwritten version Admiral Wilson gave to Howard or Sellards, and, like the latter, obviously retained by Howard. For the transmitted cablegram itself, however, everything was typed on printer tape (as both Hornblow and Howard pointed out) which was then cut and pasted onto one of these La Dépêche sheets.

(Howard and others referred to these sheets as “P.Q.” sheets. “P.Q.” are the initials of Augustin Pouyer-Quertier, who founded the Compagnie Française du Télégraphe de Paris à New York. A “P.Q.” sheet, therefore, was specifically for messages that were to be sent by underwater Atlantic telegraph cables.III.10b)

3. In the Post and Telegraph building

For what happened to the armistice message after it left the La Dépêche building, various pronouncements Howard made are the only available records. The earliest of these indicate that Howard did not himself take his cablegram for transmission.

In his 9 November 1918 letter, he told Phil Simms that a La Dépêche employee took the cablegram to the P&T building for him: the operator who printed my message out on his tape printer [and] pasted it up on a P.Q. blank . . . sent it to the wire by the newspapers messenger. III.3 And not long after this, he made the point again (in Editor & Publisher): “I suggested to the admiral that I would probably encounter some linguistic difficulties, and asked if Ensign Sellards might accompany me to get my cable off. To this he readily assented, and after I had typed a verbatim copy of the admiral’s dispatch the message was filed at the cable office by messenger from La Depeche.” III.4

Other comments he made suggest that Howard was unaware of what was going on in the P&T at the time. A postscript in his letter to Simms states that he only became aware the next day, Friday 8 November, that the local censors did not check his cablegram until two hours after its message had been delivered to New York City because people were so excited by the peace news. III.3

Similarly, in a cable to Bill Hawkins in New York City.

I WAS TOLD YESTERDAY THAT IN THE EXCITEMENT IN THE BREST POST OFFICE DUE TO THE LOCAL NEWS PAPERS BULLETIN ANNOUNCING THE ARMISTICE MY MESSAGE DID NOT REACH THE CENSORS UNTIL MORE THAN TWO HOURS AFTER THE MESSAGE HAD BEEN CABLED TO NEW YORK [Howard to Simms and Hawkins. (No date or time, but 9 November 1918) TMG3: 11/17 & 12/17]

And in Editor & Publisher, where he wrote that it was the “head of the French Bureau at Brest, Capt. Gambey” who told him “the news of the armistice had reached the cable and censorship office sufficiently ahead of [his] bulletin to allow the celebration to get under way there. In the excitement my urgent message was shot through to New York, and more than two hours later the operator bethought himself and sent the message to the censor!!!” III.4

Nonetheless, in his November 1925 letter to Cook, Howard placed himself and John Sellards unequivocally inside the P&T building:

We subsequently went to the cable office on the opposite side of the square from the newspaper office. By the time we reached the cable office [,] censors, telegraph operators and most everyone in the place was either engaged in or watching the demonstration in the Place President Wilson . . . . It was, of course, due to this ensuing confusion and the fact that [the armistice message] was filed on one of the regular blanks used for the Paris dispatches of the United Press that caused the cable operator, of his own volition, to affix a Paris date line to my message which I presumed would carry a Brest date the same as any other message filed from that point. (My italics) [Roy Howard to Fred Cook, 28 November 1925, p.2]

And his story now is that he and Sellards entered the building in the middle of great excitement and disruption caused by the peace news, and that, without Howard’s knowledge, the cable transmissions operator – not the censors – decided from the cablegram’s appearance that it was from United Press in Paris. For this reason, the operator gave it a Paris dateline and, by inference, transmitted it without waiting for the censors’ approval. The otherwise-engaged censors played no part in the matter, whereas the cablegram’s deceptive appearance certainly did.

He repeated this later version in Premature Armistice, asserting that Admiral Wilson instructed Sellards specifically to take him to the cable office to “see that he gets this message cleared through the censorship”, and that Sellards succeeded in doing so even though the censors were absent at the time:

When they entered the building, the censor room was deserted, the entire personnel having poured into the streets to join in the mass celebration . . . in the Place du Président Wilson. At Sellards’ suggestion, Howard waited in the deserted room while he took the armistice cablegram to the operating room at the cable head. Recognised there as Admiral Wilson’s confidential secretary, Sellards was able to expedite matters and stayed in the operating room until the cablegram had cleared into New York. The time was approximately 4.20 p.m. in Brest, and approximately 11.20 a.m., New York time. Afterwards, Howard learnt that no French censor ever passed on the message and that his cablegram had gone to New York City with a Paris dateline because the cable operator assumed that Simms’ name and Press-card number on the form meant it had come from the Paris office of the United Press. (My italics)

Howard concluded with echoes of Hornblow’s 1921 assessment that it was [an] unintended strategy of Howard’s that enabled him to get his cable past the local censors . . . ‘unintended’ because it is inconceivable that . . . any man, however alert, could have thought up so extraordinarily clever a devise (above):

The impossible had happened. A fantastic set of circumstances which could not have been conceived of in advance combined unintentionally and unwittingly to circumvent an air-tight military censorship which no amount of strategy and planning had ever beaten . . . . The censors were, to a man, in the street celebrating, with the rest of the populace, what they too believed to be the official announcement of the end of the war. The dispatch, not by design but by the purest accident of my being unable to use a French typewriter resembled in all its physical appearance an ordinary United Press bulletin passed by the American Press censor in Paris, and relayed via the United Press-Dépêche leased wire to Brest. Furthermore, its authenticity was vouched for by the highest American naval commander in French waters, through the medium of his own personal and confidential aide, Ensign Sellards. The combination was more perfect than if it had been planned. (My italics)

Towards the end of Premature Armistice, Howard quoted from 8 November 1918 official reports from Paris implicating Admiral Wilson in the spread of the armistice news to the United States. He was using them (ostensibly) to support a theory about the source of the false armistice news being a German spy in Paris, but they also served to corroborate that Admiral Wilson and Sellards assisted him with cablegram. [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.83-84 and 93]

Based on Howard’s timings, only about ten minutes elapsed between his and Major Cook’s arrival at Admiral Wilson’s office around 4:10 pm and the cablegram’s transmission by about 4:20 pm. About ten minutes therefore to obtain the armistice news from Admiral Wilson, have the cablegram prepared in La Dépêche, taken from there to the P&T building, and sent off to the United States. Arthur Hornblow has Howard arriving at Wilson’s office ten minutes earlier – “promptly” at 4:00 pm – which would have allowed about twenty minutes to complete the tasks.

It took six minutes for the cablegram to cross the Atlantic, Howard told Hornblow in 1921. By the time it had been cleared by military censors in New York City and forwarded to the UP office there, it was about midday local time. Within minutes, well over four hundred newspapers were receiving the peace news, and Americans began celebrating it on an unprecedented scale.

Thursday 7 November

4:20 pm to about 6:30 pm

Information from Arthur Hornblow

When Admiral Wilson released the armistice news, Hornblow was in his office at the American Army Base. A great shout [went] up around 4:30 pm from the direction of President Wilson Square, which he ignored. A few minutes later Howard, hatless, and literally wild-eyed, rushed into his office [and] exclaimed breathlessly, “Boy! I’ve scored the biggest beat in history!” In a maze of excited explanations, he told Hornblow what he had done. [Fake Armistice, June 1921, pp.7-8]

Howard objected that this was somewhat at variance with the facts. He denied rushing to Hornblow’s office immediately after sending the armistice cablegram, stating he had first returned to Admiral Wilson’s headquarters with Major Cook . . . in the hope of getting some further details. As Wilson was out, he called at General Harries’ headquarters to ascertain if the army wires had carried any additional details; and kept scurrying around right up to the hour of [their] dinner appointment trying to pick up anything that had followed the official announcement. (My italics)

He also denied being hatless and wild-eyed but admitted exclaiming that he had scored the biggest beat in history. On the latter point, however, he asked Hornblow to alter the sentence, to soften [it] a bit, in order to make his declaration sound less egotistical, adding that he would appreciate [the] courtesy. [Roy Howard to Arthur Hornblow, San Diego, June nineteenth, 1921, pp.2-4. Hornblow Papers.]

Hornblow obliged.

If the news was true, Howard probably had scored the biggest news beat of history.

Shortly after 4:30 pm, one of his men reported that Navy Headquarters was spreading official news that there was an armistice with Germany and the fighting was over. Astounded at the suddenness with which truth had been given to the odd rumor that had hovered over Brest all day, Hornblow started inquiries that quickly disclosed what had occurred. It took some time for him to find Howard, who was with Major Cook going from one official bureau to another [hoping] to procure additional information. Howard explained that Admiral Wilson had declared the news to be official and that he – Howard – had cabled to the United States announcing the war was over. Back in Hornblow’s office, he outlined what had taken place in the Admiral’s office and La Dépêche building. He reckoned his cablegram would be in time to catch the afternoon editions, and declared “There’s a day in history for you”.

Hornblow was torn between believing and not believing the peace news, primarily because G-2 (SOS) Headquarters in Paris had not so far informed him of the momentous developments and ordered him to tell General Harries the war was over. He therefore telephoned the Headquarters (no time) and to their apparent astonishment told them about the celebrations in Brest. No word of any armistice had reached [them], only that German delegates were expected to meet Marshal Foch that afternoon at five. Hornblow suggested they make immediate inquiries at the French Ministry of War and report back to him.

Failure to verify the armistice news did not seem to worry Howard unduly. He simply refused to accept that Admiral Wilson’s “office” in Paris may have misinformed him; and argued that the American Embassy must have had the armistice news ahead of G-2 (SOS) Headquarters. General Harries telephoned to Hornblow that only when verification of the armistice news came through either from Paris or General Pershing’s AEF Headquarters at Chaumont would he believe the war was over; and that before then there would be no peace celebrations at the Army Base. [Amazing Armistice, November 1921, pp.93-94 and 96]

Thus, instead of having Howard rush into his office with the peace news, as in Fake Armistice, in Amazing Armistice, after hearing about Admiral Wilson’s news, Hornblow went to look for Howard, eventually found him and Major Cook going around Brest hoping to pick up more about the armistice, and then took Howard back to his office from where he telephoned Paris and was told there was no German armistice yet.

“There’s a day in history for you” was obviously Hornblow’s alternative ‘softened’ and ‘less egotistical’ exclamation to Howard’s “Boy! I’ve scored the biggest beat in history!” – one that carried all the irony the words held for Howard personally.

The sentences “Astounded at the suddenness with which truth had been given to the odd rumor that had hovered over Brest all day”, and “[the rumor] was present in Brest before Admiral Wilson’s receipt of the message from Paris”, were inserted in Amazing Armistice because Howard had insisted that the rumours were widespread in Brest hours before Admiral Wilson’s news that the war was over.

By the time Hornblow telephoned G-2 (SOS) Paris Headquarters – sometime after 4:30 pm seemingly – false armistice rumours had been spreading around Paris and to other parts of France since shortly before midday. And the Headquarters had been investigating them and communicating with AEF Headquarters in Chaumont and Services of Supply Headquarters in Tours about them. III.11 Their reply to Hornblow that “no word of any armistice had reached [them]” was true only in the sense that they had no confirmed official news of a German armistice, so it is odd that they did not warn him about the rumours. (Perhaps they did, and Hornblow asked them to contact him when they were able to say whether the German delegates had signed an armistice soon after their expected meeting with Marshal Foch around 5:00 pm.)

Hornblow had altered Fake Armistice to say that he found Howard with Fred Cook, sometime after 4:30 pm, searching for the latest about an armistice – as Howard had insisted he and Cook were doing. But after leaving Navy Headquarters (alone) to give General Harries the peace news, Cook stated that he did not see Howard again until Friday 8 November – in the La Dépêche building using the telegraph to Paris. III.7

From Premature Armistice

In Premature Armistice, after sending his armistice cablegram Howard does not spend time with Cook searching for armistice news, or going to Hornblow’s office, telling him what he had done, and learning that Hornblow now doubted that Germany had agreed to stop fighting. He recounts only that he and Sellards (my italics) made their way back, through crowds celebrating the peace news, to Admiral Wilson’s office; that the Admiral was no longer there; that he then walked to his hotel to write a “follow” to his armistice cablegram; and then waited until it was time to go to dinner with Hornblow and two or three of his officer friends. At first he assumed American newsmen in Paris had already sent the story to the United States. But then, because Admiral Wilson’s news had travelled by military wire from Paris, he reasoned that there was an outside chance Brest had the news very soon after it broke in Paris. The advantage of being in Brest, he concluded, had helped him beat the competition in Paris to be the first with the peace news in New York City. [Premature Armistice 1936, p.85]

Between 4:30 pm and 5:00 pm, Howard certainly became aware that Admiral Wilson’s armistice news from Paris was not yet circulating in Paris – his communications with the UP office there made this clear. III.12 But he did not leave the P&T building with Ensign Sellards to return to Navy Headquarters; and, as Admiral Wilson was not there, return alone to his hotel where he prepared his second cablegram for the New York City office.

He did return to Navy Headquarters – but on his own, shortly after 5:00 pm – to see Admiral Wilson to ask him for news of the armistice: John Sellards told Wilson that “none of us knew it at your Headquarters that the message had actually been sent until Mr. Howard came slinking back again filled with misgivings because he began to wonder if he had acted too hastily.” III.14 And still on his own, he then, presumably, walked to the American Army Base, arriving what would have been some time after this. Hornblow said Howard was with him there when he telephoned G-2 (SOS) HQ in Paris for a confirmation or refutal of the armistice news.The reply from Paris did not arrive at the Army Base until 9:00 pm, before which Howard went back to La Dépêche to send his 6:30 pm cable to Bill Hawkins in New York City. After this, he probably did return to his hotel and wait there before going to dinner (no time stated) with Hornblow and his colleagues, as he claimed in his memoir.

French denials of the armistice news

Not much more than an hour after Howard’s cablegram, Colonel Maurice Laureau, the French Government’s liaison officer with the American Army in Brest, turned up at the Army Base, protested loudly to General Harries that the peace news was not true and demanded that the celebrations in the town be stopped. Laureau reported the matter to his superiors in Paris the next day, recording that around 5:30 pm on 7 November the Brest Maritime Prefect’s Headquarters reported to him that the armistice news was misinformation emanating from an official French source; that he immediately telephoned this to the American Army Base; then went over there to speak to General Harries, who eventually contacted the American authorities about the news. Around 9:00 pm – nearly three and a half hours later – the authorities assured the General there was no German armistice yet. III.15; III.16

Fred Cook described Laureau’s intervention in his November 1925 newspaper feature. III.7 It is not in Hornblow’s articles; but Howard referred to French doubts about the armistice news in his letter to Phil Simms; in a cable to Bill Hawkins in New York City; and in Editor & Publisher. [Howard to Phil Simms, November 9, 1918, p3; Howard to Bill Hawkins, 9 November 1918. TMG3: 15/17; Editor & Publisher, November 23, 1918, p18]

Cook presumably was at the Army Base when Colonel Laureau arrived (having earlier left Navy Headquarters without Howard). Hornblow was there as well. Howard was in the La Dépêche building at least until 5:00 pm, communicating with his Paris office about his armistice cablegram. But sometime after that, and until around 6:30 pm, he too was at the Army Base before he went back to La Dépêche to send his second armistice cablegram. In Amazing Armistice, Hornblow talks about Howard’s being there with him around that time – not in the Continental Hotel as Howard maintained in Premature Armistice.

6:30 pm to Midnight

The French denials preceded the dinner Howard suggested earlier in the day for Hornblow and some of his colleagues, and were responsible for its interruption by a Signal Corps orderly: they shaped the rest of Howard’s evening.

An Interrupted Dinner

For the dinner, they went to La Brasserie de la Marine which was also on President Wilson Square and quite close to Admiral Wilson’s Headquarters. III.6 They were there after 6:30 pm, that is, after Howard’s Brest-celebrating cablegram to the New York City office, for in his 9 November letter to Phil Simms, Howard related that, having filed “a little item re Brest being the first city in France to get the news”, he “then went to dinner with a couple of Intelligence officers [he] had met”. III.3

Hornblow’s and Howard’s versions of what happened in the restaurant differ sharply, even though Hornblow later changed the following vivid Fake Armistice portrayal to suit Howard.

At Howard’s request, and growing constantly more infected by the spirit of the great victory, I rounded up a band of cronies for a dinner party to be given by Howard by way of celebrating his ‘scoop’ . . . . Six of us gathered around the tiny table that Howard had managed to wangle at La Brasserie de la Marine, Brest’s Delmonico, and, that evening, a pandemonium of gaiety. (With Hornblow were his assistant intelligence officer, two navy headquarters officers, and a French liaison service officer.)

Through the windows poured the din of rejoicing in the streets. The Brasserie was alive with flags, confetti and streamers that had all leaped suddenly into being from nowhere, and the usual clatter of dishes was replaced by the yells and songs of several hundred unrestrained throats. Two pretty girls danced recklessly on a narrow table packed tightly against ours, while their Yankee escorts roared a jazz accompaniment. On our table danced nothing less solemn than a collection of magnums – Moët, 1904. I do not recall seeing any food anywhere . . . . As a matter of fact, we had ordered some, but the restaurant could find neither the means of serving it nor the place to put it! What a setting for a celebration of the ‘greatest beat in history’! With the whole world seemingly helping us celebrate!

Then suddenly came the crash, just as it had to come . . . . I had left word for any wire from Paris to be sent to me immediately. In the midst of a din that was getting louder momentarily, a signal corps orderly entered the room unnoticed and made for our table. A feeling of grave apprehension seized me as I grasped and opened the message that was handed me. I felt Howard’s eye on me as I read, and the blood marched to my head.

The communication was in intelligence code, and the process of translation was slow and fearful. Finally it was done . . . . The message said: ‘Armistice report untrue. War Ministry issues absolute denial and declares enemy plenipotentiaries to be still on way through lines. Cannot meet Foch until evening. Wire full details of local hoax immediately.’

It was signed by Major Robertson, my immediate superior at Paris.

I shall draw a swift curtain over the cruel scene of reaction. Howard’s white, drawn face as he realized what he had done, as he read in the words I handed him his own doom and that of the United Press. His exclamation that he would give a million dollars to recall his cable to New York. Our filing out with him back to the Continental, leaving behind us, undisillusioned, the tragically joyous throngs celebrating a peace that wasn’t a peace . . . . We stayed with Howard as long as we could that night, with the pitiful hope of cheering him up or, at least, trying to keep his thoughts off the suicidal! [Fake Armistice, June 1921, pp.12-13]

Howard objected to the idea that he had organised a party to celebrate his armistice scoop, and that they all went out to paint the village pink. He reminded Hornblow that he had invited him to have dinner during their lunch at the Navy Club – hours before either of them had any intimation of what was to transpire – and thought he should change it for the sake of having the record written straight.

He also disliked Hornblow’s assessment of the effects on him of the denial of the armistice news: I really think that you swung one a little bit low in your reference to suicide. It isn’t the Irish way, old top. I might have contemplated murder that night – but never suicide. He felt Hornblow could emphasize all the dramatics of the denial of the peace news without having it quite so heavily at [his] expense. [Roy Howard to Arthur Hornblow, San Diego, June nineteenth, 1921, pp.4-5. Hornblow Papers.]

Hornblow again altered the text, so that in Amazing Armistice:

He avoided the impression that the dinner was a celebration of Howard’s ‘scoop’ by writing during our luncheon and before the storm had broken, Howard had asked me to dine with him that night, little thinking that he was, in effect, asking me to an armistice celebration. He elaborated on the hectic, joyful scene in the crowded restaurant; removed the names of his associates and the champagne purchases; and omitted the reference to Howard’s suicidal thoughts – I shall draw a swift curtain over the cruel scene of reaction: Howard’s white, drawn face as he realized what he had done, as he read in the words I handed him his own doom and that of the United Press. [Amazing Armistice, November 1921, pp.95-97]

In 1936, Howard gave the dinner scene just a short paragraph, and changed what Hornblow had said about the orderly.

We had not yet ordered our dinner – not even the drinks which were to precede it.

An orderly from Admiral Wilson turned up at the restaurant to warn Howard that the armistice news had not been confirmed; the Admiral had been unable to get in touch [with Howard] personally because he had left Brest for the evening. [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.85-86] (My italics)

In his 1921 letter about Fake Armistice, Howard had acknowledged that the orderly was looking for Hornblow: logically it was Hornblow the orderly wanted and to whom he handed the message, not Howard. The message itself was no doubt the reply from G-2 (SOS) HQ in Paris to the enquiry General Harries had ordered after Colonel Laureau’s protests at the Army Base (I had left word for any wire from Paris to be sent to me immediately). The time, therefore, would have been after 9:00 pm and the receipt of the reply from Paris.

Looking for Admiral Wilson

In his earliest accounts, Howard spent the rest of the evening alone, claiming that after the dinner (not interrupted), he went to the La Dépêche office where he heard that the French were denying the armistice news; searched for Admiral Wilson to see whether he had anything more about it; eventually found him and was told the news was not confirmed; sent another cablegram from La Dépêche to the New York City office to report this; and remained at the leased wire until midnight. III.3; III.4

But in Premature Armistice he claimed that after leaving the restaurant he and Hornblow “went immediately to the office of La Dépêche” to send a dispatch to New York City. According to Hornblow in Fake Armistice, he and his colleagues took Howard back to the Continental Hotel from the restaurant and stayed with him there. Howard ignored this point, but reproached Hornblow for omitting to say that the two of them went to find Admiral Wilson after the interrupted dinner. He reminded him that when they left the Brasserie de la Marine:

While I naturally felt that an element of great doubt had been injected into the [armistice] story by this denial, I was by no means yet satisfied that the report was untrue. As a matter of fact my confidence in its authenticity was not seriously shaken at any time until you and I having failed to locate Admiral Wilson at his office or at his home, called at the house where he was attending a dinner party – as I recall it was either the Mayor of Brest [or] the French Admiral commanding the base – and there had sent out to us the Admiral’s own report that the information was (not untrue, please recall) [but] ‘premature’. Adding, with some annoyance: I am considerably at a loss why it was that you entirely eliminated mention of this feature of the evening, one which to me has always seemed significant. [Roy Howard to Arthur Hornblow, San Diego, June nineteenth, 1921, p.5. Hornblow Papers.]

Hornblow duly amended Amazing Armistice.

Howard spent most of the night trying to get information.

On leaving the restaurant, he accompanied Howard to the Continental Hotel. A revival of hope, an inability to believe [the denial of the armistice news] impelled Howard to go in search of Admiral Wilson. The two of us finally located him dining en famille with a French local official. Here, Sellards came out to tell them that the armistice news was premature.

Howard seized upon this, desperately hoping that premature meant true but not properly released, and that the armistice news would be officially declared later on. He spent most of the night trying to get information from his own Paris office. But when he succeeded, his hopes evaporated: ‘premature’ meant untrue. The world collapsed about Howard’s ears. His biggest ‘beat’ in the history of journalism had turned cruelly into [his] biggest ‘bloomer’. [Amazing Armistice, November 1921, p.97]

Most surprisingly therefore, in Howard’s memoir there is no episode about finding Admiral Wilson during the evening: he omitted what he told Phil Simms he did, what he recounted in Editor & Publisher in November 1918, and had criticised Hornblow for overlooking.

Having read the orderly’s message he said was for him from Admiral Wilson, accompanied by Lieutenant Hornblow, [he] went immediately to the office of La Dépêche [and] wrote another dispatch, stating that Admiral Wilson’s first bulletin had been followed by a second stating that the original statement was now held to be unconfirmable. This dispatch was filed at Brest approximately two hours after the first one (which would have been around 6:20 pm by Howard’s timings). Had it been delivered [as quickly] as the first, the correction would have been in the United Press office in New York some time after one p.m. However, for reasons which have to this day never been satisfactorily explained, this second bulletin, which would have enabled the United Press to correct the original error within two hours, was not delivered to the United Press in New York until shortly before noon on the following day, Friday, November 8. [Premature Armistice 1936, pp.85-86]

However, Howard did not go to La Dépêche (just across the square from the restaurant) with this ‘unconfirmable’ news for the New York City office “approximately two hours after” sending Admiral Wilson’s armistice news. He did go to La Dépêche around that time, but with the 6:30 pm news he described to Phil Simms as a “a little item re Brest being the first city in France to get the news”. He did send a cablegram that the armistice news was “unconfirmable”, but not until much later that evening and only after he had located Admiral Wilson at the French Admiral’s house (as in his Editor & Publisher exclusive). The fact is that Howard and Hornblow abandoned their dinner because of Colonel Laureau’s news and then went in search of Admiral Wilson to find out about the French denial of the armistice news. And this means that Howard and Hornblow left the restaurant sometime after General Harries’ receipt of the American authorities’ reply around 9:00 pm. Admiral Wilson’s papers verify that Howard interrupted his evening dinner with a French Admiral. He was at the latter’s house and already knew that the armistice news from Jackson had been cancelled, although whether he had ordered this to be announced is uncertain. And he may also already have known about Colonel Laureau’s news. I. Admiral Henry. B. Wilson Papers

Howard had not been mistaken about the orderly looking for him in the restaurant or about going straight to La Dépêche to send the ‘unconfirmable’ cablegram to New York City as his second one that day. He misreported these details in 1936, for a reason which seems to be explained by an announcement Bill Hawkins made from the New York City office on Friday 8 November 1918 that Howard’s second cablegram was his armistice-unconfirmable one, and that this had been held up by American censors until Friday, thereby delaying UP’s withdrawal of the armistice news for many hours.

Friday 8 November

From Arthur Hornblow