The Jackson Armistice Telegram takes its name from Captain Richard H. Jackson (1866-1971) who had arrived in Paris in June 1917 as the “Representative of the United States Navy Department”, “senior United States Naval Officer on shore in France”, commander of US “naval and aviation bases” in France, and commanding officer at the US Navy Headquarters in Paris. In these capacities, he acted under the orders of Vice-Admiral William S. Sims, the Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters whose headquarters were in London. He was also Sims’ liaison officer at the French Ministry of Marine in Paris, and was instructed to “confer” with Admiral H. B. Wilson at US Navy Headquarters in Brest when the latter became “Senior Naval Officer afloat in French Waters” during late October 1917.

When Jackson arrived in Paris, the US Naval Attaché at the American Embassy was Lieutenant Commander (later Captain) W. R. Sayles, who was promoted in January 1918 to the new post of “Intelligence Officer of the United States Naval Forces in France”. Jackson, retaining his other responsibilities, became the US Naval Attaché in June 1918 and, as such, “Liaison Officer between [Admiral Wilson in Brest] and the French Authorities in Paris”. As Wilson’s Liaison Officer, he was considered to be a member of Wilson’s own staff.1

Throughout his time in Paris, Jackson’s base was the US Navy Headquarters building at 4 Place d’Iéna. As Naval Attaché between June and November 1918, he was officially a member of the American Embassy Staff with an office in the Embassy itself. He remained in his Navy Headquarters office, however, and placed Lieutenant Commander Charles O. Maas, W. R. Sayles’s Assistant Naval Attaché since October 1917, in charge of the Embassy office. By his own account, Maas thus became responsible for “most of the work connected with Embassy matters, and [was] in intimate touch with both the Ambassador [William Sharp] and the various Secretaries of the Embassy in all matters in which the services of the Naval Attaché were requested”. On 7 November 1918, Lieutenant Moncure Robinson became Maas’s assistant at the Embassy office.2

The Jackson Armistice Telegram

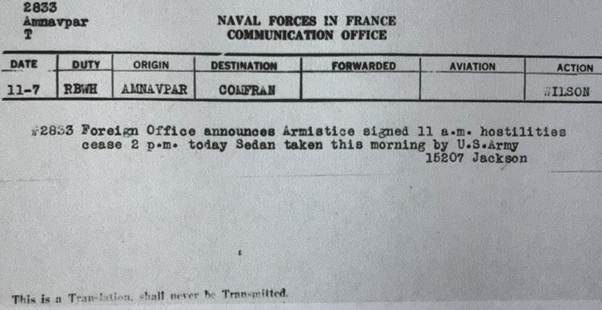

The message in this telegram was behind all the afternoon false armistice cablegrams that reached Britain and the United States on 7 November 1918. It read, “[French] Foreign Office announces Armistice signed 11 a.m. hostilities cease 2 p.m. today Sedan taken this morning by U.S. Army”. (See the first image below.)

It was received by the American Embassy during mid-afternoon, telephoned from here to the US Navy Headquarters close by, and then telegraphed from here to Admiral H. B. Wilson at his headquarters in Brest (on the Britanny Peninsula) and possibly also to US Navy Headquarters in London.3

The message’s arrival at the American Embassy

In November 1918, the American Embassy was situated at 5 Chaillot Street (rue de Chaillot). It is not known exactly when during the afternoon the message arrived at the Embassy, or how it was delivered – by private telegraph, telephone, or courier. Indeed, the Embassy’s handling of the false armistice message has been obscured by what was probably a deliberate withholding of information about what happened there on 7 November 1918, compounded by hardly credible ‘explanations’ postulating a German false-armistice-news conspiracy. Namely, Arthur Hornblow’s theory that a German spy concocted the false news and fooled Embassy staff into believing he was sending it from the French War Ministry; Roy Howard’s variation on this that the spy claimed to be sending the news from the Foreign Affairs Ministry; and Moses Cook’s theory that the spy contacted the Navy Headquarters directly and fooled a duty officer into believing he was an official at the American Embassy telephoning the news from there.4

However, coming purportedly from the French Foreign Office, the message was presumably in French originally and was received over the Embassy’s own telegraph wire and through its own ticker tape equipment. Inside the Embassy, it would have been translated into English and sent first to Ambassador W. G. Sharp’s office for his information and action. Other obvious ‘need-to-know’ recipients of news of this nature were the Military and Naval Attachés on the Embassy Staff, and President Wilson’s Special Representative in Paris, Edward House. Military Attaché Warburton probably decided not to believe it, given his mistake over the morning armistice news;3 that Lieutenant Commander Maas handled it in Naval Attaché Jackson’s office in the Embassy (it is unlikely that Maas’s new assistant at the Embassy, Lieutenant Moncure Robinson, was on duty on his first day in post); and that Edward House heard the news at his residence and offices on University Street (rue de l’Université), across the River Seine from the French Foreign Office.

From the Embassy by telephone to US Navy Headquarters

US Navy Headquarters were in the Jena Hotel building (Hôtel d’Iéna) at 4 Jena Square (Place d’Iéna), a few minutes’ walk away from the Embassy. According to eyewitness Moses Cook, during mid-afternoon on 7 November the duty ‘communication officer’ at the headquarters – a Lieutenant Barler – rushed into the signal room with a message from the Embassy and told Cook, “chief radioman in charge of the wire room”, that a “commander” at the Embassy had just telephoned it to him. Cook claimed later that he knew who the commander was, but had since forgotten his name.5 This was most likely Lieutenant Commander Maas.

At Navy Headquarters, the armistice message was obviously intended for Captain Jackson’s attention and action; but it is not known where he was when Lieutenant Barler received it – whether he was somewhere in the building or somewhere else (perhaps preparing to depart for Washington, D.C., where he was due to take up a new appointment in the Navy Department).

Sent from the Signal Room to US Navy Headquarters in Brest

Lieutenant Barler handed the Embassy’s telephone message to Moses Cook and ordered it to be transmitted without delay. Cook passed the message to the operator of the “Brest Wire” – a Lieutenant Emmett King – who telegraphed it in unencrypted Morse Code to Navy Headquarters in Brest. At the end of the message, the time and authorization “15207 Jackson” (3:20 pm, 7 November) and instruction “This is a Translation, shall never be Transmitted” were added. About twenty minutes later, Barler rushed back into the wire room and tried to have the message stopped – “it’s a fake” he shouted. But it was too late: the message had already arrived in Brest and been forwarded from there to Washington, D.C.5 (Admiral Wilson and the US Navy Headquarters in London received it not long before 4:00 pm; Roy Howard cabled it to New York City by 4:30 pm; and United Press received it by about midday New York time, 5:00 pm French time.)

There is good reason to believe that Captain Jackson did not know about the armistice message before it was transmitted. Admiral Wilson intimated as much to Arthur Hornblow in July 1921. And in May 1941, Moses Cook told Hornblow this was so: Captain Jackson “was very much upset about it”, demanded to know what had happened and who had released the message and, as “the fault was with the lieutenant”, reprimanded Barler and had him “sent home” not long afterwards.5

Obviously, if Jackson did not see the message when it reached Navy Headquarters then someone else must have decided to transmit it with Jackson’s name on it. And according to Moses Cook, this was quite normal: “all messages leaving our headquarters had to be signed ‘Jackson’ as a matter of routine, but he did not see every dispatch that was sent.”5 So, did Barler, in Jackson’s absence, decide the armistice message should go off to Brest without delay and add Jackson’s name to it himself? Given the punishment Moses Cook claims befell the lieutenant, it appears that he did.

At US Navy Headquarters in Brest

On its arrival in Brest (time not specified, but shortly before 4:00 pm) the armistice message, in “plain English” Morse Code, was transcribed for Admiral Wilson’s information and action, and transferred to a blank naval telegram form. The following is an image of the completed form as put together at Wilson’s Headquarters. It is available in the US Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Archive, but has been incorrectly listed as an 11 November 1918 telegram, included in a group of telegrams announcing the Armistice of 11 November 1918, and thereby rendered virtually invisible as a historically important document in its own right.6

The sheet shows the (abbreviated) origin of the message from the American Navy in Paris; and its (abbreviated) destination – (US Navy) Commander in France.

Admiral Wilson accepted the armistice message at face value – with Jackson’s name on it, he had no reason to doubt its authenticity; and (allegedly) informed the Navy Department in Washington, D.C., that “Headquarters [in Paris] reports armistice signed Wilson” – this arrived at 12:10 pm EST.3 He also ordered the news to be taken to the local French newspaper (whose building was close by), to be announced to people in the square outside his headquarters, and, with consequences impossible to foresee, gave a copy of it to Roy Howard of United Press, who had arrived at his headquarters just a few minutes beforehand. Howard immediately rushed off to cable the message to New York City, where it arrived around midday EST.

According to Admiral Wilson, around 6:00 pm French time – “two hours” after the armistice message had arrived in Brest – he received another message from Jackson, in code this time, which read: “Rush signature Armistice unconfirmed German representatives rush [reach?] borders 6 P.M. . . . Let it be known at once, thereby killing the previous report.”7 Wilson (again allegedly) then informed the Navy Department that “headquarters [in Paris] report error in signature” – this arrived at 1:10 pm local time, 6:10 pm French time.3

After the war

In July 1919, J. A. Carey, Admiral Wilson’s former “Flag Secretary”, offered (through an intermediary) to sell to Hugh Baillie, the Washington, D.C., United Press manager what he said was the “original” Jackson Armistice Telegram. But in a letter to Roy Howard dated 11 August 1919, a United Press official in Oklahoma City, L. B. Mickel, stated that the “original [telegram] is in [Admiral] Wilson’s file”. Mickel told Howard that a “copy” of the original telegram had been “made” by a ”wireless operator [unnamed] in Wilson’s office at Brest”, and that M. R. Toomer, a member of the Oklahoma News staff, had “taken” a copy of the wireless operator’s copy. Mickel sent this information to Roy Howard, with a representation (shown below) of the wireless operator’s copy, on a single sheet of paper headed “United Press Associations”.8

J. A. Carey’s so-called “original” and the Brest wireless operator’s so-called “copy” of the original still in Admiral Wilson’s file were most likely unauthorized duplicates of the Jackson Armistice Telegram made as souvenirs of 7 November 1918 events. (And they may well have been one and the same rather than two separate copies.) Whether other duplicates were made and still exist is not known. But in the United States there is at least one (in private possession for more than two generations) that is almost identical to the first image shown of the Jackson Armistice Telegram found in the US Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Archive (image shown above).

Some comments on, and inferences from the Jackson Armistice Telegram

As shown on the telegram’s image above, the armistice message telephoned from the American Embassy to the US Navy Headquarters in Paris reads: “Foreign Office announces Armistice signed 11 a.m. hostilities cease 2 p.m. today Sedan taken this morning by U.S. Army 15207 Jackson

This is a Translation, shall never be Transmitted”

“Foreign Office” denotes the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministère des Affaires Étrangères), situated at 37 Quay d’Orsay on the left bank of the River Seine. The phrase “Foreign Office announces” suggests that the French Foreign Ministry released this armistice news – that is, released military news usually made public by the French War Ministry. As it seems unlikely that the Foreign Ministry would have pre-empted the War Ministry in this way, it is reasonable to suggest that the Foreign Ministry was actually passing on to diplomatic establishments in Paris, especially those of France’s allies against Germany, afternoon armistice news it had received from the War Ministry, and this is the assumption made here.

The message gives 11:00 am as the time the Armistice-signing occurred. The American Army G-2 (SOS) Report, however, says it was a 10:00 am signing.9 Whether these are Allied or German times is not certain, and there is nothing in the Jackson armistice message or G-2 (SOS) Report that suggests why the supposed signing had occurred at 10:00 am or 11:00 am, indicates where it took place, or expands on the 2:00 pm cessation-of-hostilities detail. (It is presumed here that the times given in the message are French times, not German.)

The morning armistice-signing detail, however, apparently confirms the armistice-signed news which Major Warburton, the American Military Attaché, had forwarded to Washington before midday, and which the G-2 (SOS) Report claimed the French War Ministry had released; and the 2:00 pm cessation-of-hostilities detail brings to mind Warburton’s ‘rumours of an afternoon cease-fire’ explanation for the false armistice news which he sent to the US Military Intelligence Department.10 But why would the French War Ministry send out an affirmation of its morning armistice-news for the Foreign Ministry to circulate during the afternoon?

The “15207 Jackson” sign-off on the armistice message indicates that it had arrived at US Navy Headquarters in Paris sometime before 3:20 pm. Therefore, it must have arrived a little earlier than 3:20 pm at the American Embassy (before being telephoned from here to the Navy Headquarters), and even earlier at the French Foreign Ministry itself, but exactly when the French War Ministry sent out the information is not known.

(The translated “hostilities cease 2 p.m. today” wording of the message suggests that hostilities had not yet ceased when the message was put together, implying that it was prepared before 2:00 pm French time/3:00 pm German time on 7 November. The misinformation about the taking of Sedan by the American Army had started circulating in Paris during late morning and early afternoon.11)

Significantly, by 3:20 pm (the message’s sign-off time) both the German and French cease-fires had come into effect on that part of the Western Front where Marshal Foch had told the German armistice delegation to cross into France: the German cease-fire having started there at 2:00 pm French time/3:00 pm German time, the French cease-fire at 3:00 pm French time/4:00 pm German time. The French War Ministry would have known of these events soon after they occurred and, conceivably, passed on information about them to other French Ministries. Considering these circumstances, it is reasonable to assume that French War Ministry officials took the German and French afternoon cease-fires to be confirmation of the armistice news they had released before midday, and which they now reaffirmed with this afternoon armistice news not very long after both cease-fires were in effect and the Sedan-taken news was already circulating.12

© James Smith (June 2025).

REFERENCES

DOCUMENT SOURCES

A) Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs. Military Intelligence Division. Security Classified Correspondence and Reports, 1917-1941. Record Group 165, United States National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

B) Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918. Supplement 1, The World War, Volume I. Part 1: The Continuation and Conclusion of the War – Participation of the United States. Editor: Joseph V. Fuller. (US Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. 1933.) [Online]

C) Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: The Lansing Papers, 1914-1920. Volume II. ‘Memorandum by the Secretary of State. November 7, 1918.’ Document 126. Editors: Cyril Wynne; E. Wilder Spaulding; E. R. Perkins. (US Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. 1940.) [Online]

NOTES

1. See: Biographical Chronology of Richard H. Jackson, available online from the United States Naval Academy, Nimitz Library: Richard H. Jackson papers, 1802-1988 (Bulk 1883-1971). Also: Vice Admiral William S. Sims to Captain Richard H. Jackson, London, 5th July, 1917, available online from the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), Documentary Histories, WWI. And, Manley R. Irwin, Under Administrative Stress: The U.S. Navy Base, Brest, France, 1917. Available online. In the January 1925 Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps, p3, he is listed as a Rear Admiral and Assistant Chief of Naval Operations. He became Rear Admiral in June 1921 (p364).

Some of Jackson’s papers are deposited at Stanford University, but throw no light on the 7 November armistice news or his involvement in it. Richard Harrison Jackson Papers, 1917-1930. Stanford University – Hoover Institution Library and Archives.

2. Lieutenant Commander Charles O. Maas compiled A History of the Office of the United States Naval Attaché, American Embassy, Paris, France, during the period embraced by the participation of the United States in the war of 1914-1918, for the US Navy’s Historical Section. Its unbound typewritten pages are held by the US National Archives and Records Service, Washington, D.C. (File Unit, E-9-a, 12302. NAID, 196039947 and 196039948, Container ID 745, Record Group 38. The separate typewritten pages were put together as a Print Book in 1977. Maas died in France on 21 July 1919, what must have been a short time after he completed the history. (Brief entry about him in the Columbia University Archives, under Law School, Class Year 1892.) In the Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and Marine Corps, January 1, 1919, pp711;1171, he is listed as “Charles Oscar Maas, born 28 Nov. [18]70. Lieut. Commander U.S.N.R.F. Enrolled, 27 Aug. [19]17.

3. See the articles ‘False Armistice Cablegrams from France’ and ‘Roy Howard’s Search for Information about the False Armistice’ on this website.

4. See the article ‘False Armistice Conspiracy Theories’ on this website.

5. See the article ‘Arthur Hornblow’s Information about the Jackson Armistice Telegram’ on this website.

6. This Jackson Armistice Telegram surprisingly turned up during online searches made in the Naval History and Heritage Command Archive in Washington, D.C.

7. See the article ‘Admiral H. B. Wilson and Roy Howard’s Armistice Cablegram’ on this website.

8. See ‘Roy Howard’s Search for Information about the False Armistice’ on this website. Perhaps the Jackson Armistice Telegram found in the Naval History and Heritage Command Archive in Washington, D.C., is the original from Admiral Wilson’s office in Brest. The Oklahoma News was a United Press news agency subscriber; it published Howard’s false armistice news from Brest on 7 November 1918.

9. See ‘The American Army G-2 (SOS) Report on the False Armistice News of 7 November 1918.

10. See the article ‘False Armistice Cablegrams from France’ on this website.

11. The taking of Sedan misinformation was attributed in some quarters to a New York Times war correspondent, Edwin L. James, whose bulletin that day allegedly reported that “Sedan was set on fire by the Germans before they evacuated it” during their “very rapid” retreat. The Auckland Star, 8 November 1918, p5, under “The Americans took Sedan just before the armistice was signed”; and the New Zealand Herald, 9 November 1918, p7, both cited reports from New York on 7 November. Accessible online. See ‘The False Armistice in France’ article on this website.

12. See ‘Explaining the Origins of the 7 November 1918 False Armistice News’ on this website’.